To see Dean Sossin’s companion article about tuition transparency, click here!

Have you ever wondered who sets the level of tuition at Osgoode and how they do it? Maybe the better question is: who hasn’t?

The amount of tuition we pay has a direct effect on the choices we make after law school. First year students entering Osgoode in September 2012 paid $20,564.28 in tuition and $890.68 in ancillary fees, for a total cost of $21,454.96. While tuition has increased 8% each year since the 2006-2007 academic year, a new provincial tuition framework has now capped increases at 5%. However, when including off-campus living expenses conservatively estimated by the Office of Student Financial Services at $18,750 each year and without including personal savings or financial aid, each 1L is still likely to graduate with over $100,000 in debt. For a law school with a “commitment to public law, social justice, and ethical lawyering,” this severely restricts the ability of students to pursue careers in smaller law firms that are critical to improving access to justice. This also disproportionately affects the ability of those in lower socioeconomic and equity-seeking groups to complete a law degree at Osgoode.

Your 2012-2013 Student Caucus approached Dean Sossin and Osgoode’s new Executive Officer, Phyllis Lepore Babcock, to discuss how tuition is determined. The Office of the Executive Officer falls under the purview of the Dean’s Office. Two of Phyllis’ many responsibilities include working with Osgoode’s various units on the law school budget and being accountable for how money is spent. The York University Board of Governors is responsible for setting the tuition which Osgoode students pay.

Both the Dean and Phyllis are supportive of increasing transparency in tuition-setting and are committed to engaging students in a conversation on tuition. While this article will not answer all students’ questions, it will hopefully spark a dialogue that will continue into the future.

How are tuition fees set?

A now-expired provincial tuition framework for professional programs allowed Osgoode to increase tuition by a maximum of 8% for 1L students and 4% for those in 2L and 3L. On March 28, 2013, the province released a new tuition framework that capped increases at 5% each year for the next four academic years.

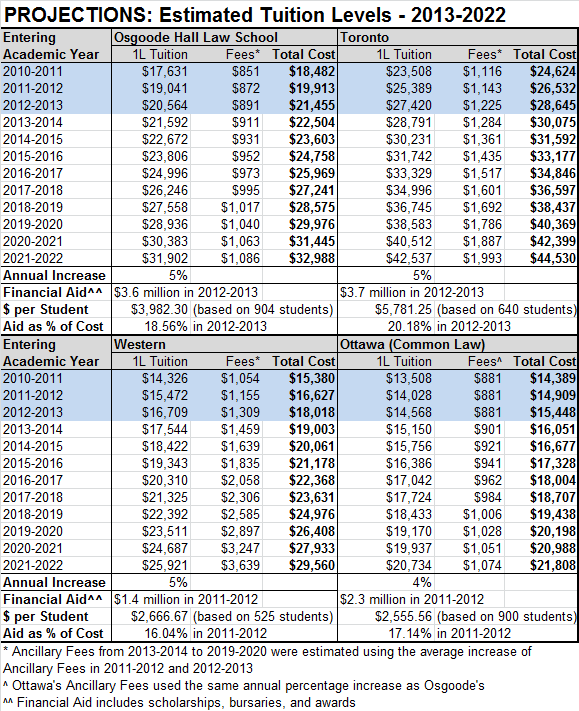

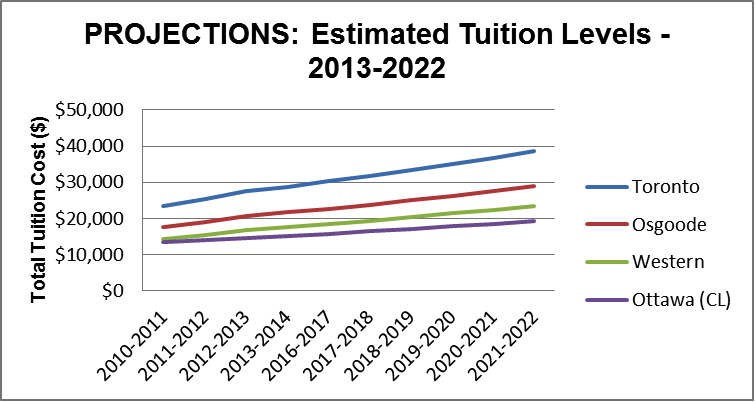

To compare, the annual percentage increase in tuition and total financial aid for the law faculties at the University of Toronto (“Toronto”), University of Western Ontario (“Western”), and the University of Ottawa (“Ottawa”) were found. Toronto and Western follow the same percentage increases as Osgoode, while Ottawa’s tuition rises 4% every year. Ancillary fees were estimated using the average growth rate of each school’s fees between 2010-2012. If Osgoode, Toronto, and Western increase tuition at the new 5% maximum while Ottawa maintains their 4% increase, the cost of a legal education will be as follows:

Is it true that an Osgoode education may exceed $33,000 in 9 years?

The new 5% annual 1L increase means that tuition fees double every 15 years. This also means that in 5 years, Osgoode’s annual tuition and ancillary fees will likely amount to over $27,000. In 9 years, attending Osgoode may cost over $33,000 each year – and that’s not including rising living costs. The situation is even more ominous at the University of Toronto, where a legal education is estimated to exceed $36,000 in 5 years and $44,000 in 9 years. Because Ottawa’s law faculty has lower current tuition and increases tuition by 4% every year, the total cost to attend Ottawa’s law school in 9 years could be roughly what Osgoode 1L students pay today, just over $21,000.

How are annual tuition increases of 5% justified?

According to Phyllis, there are three reasons why Osgoode’s tuition’s increases are justified. First, additional revenues are needed to enhance the quality of Osgoode’s academic programs and student experience, such as the establishment of the Office of Experiential Education and the hiring of a new Student Success & Wellness Counsellor. Second, new funds are necessary to increase Osgoode’s complement of full-time faculty. Third, increasing revenues are necessary to pay for increasing salary and benefit costs, which rise in accordance with collective bargaining agreements.

This is similar to the academic inflation justification made by Toronto’s administration in a recent document released entitled “Tuition and Financial Aid Discussion Document: 2006 to 2012” released in response to a student petition (www.tuitionpetition.ca) against tuition increases at their school (which is rising at the fastest rate in Ontario because their tuition was highest in the province when the tuition framework was released). According to the report, increases are justified because there has been almost no growth in government funding and the law school’s major costs (e.g. academic salaries, student services, and financial aid) have increased by an average 4.6% per year since 2006-2007. Like Osgoode, the Toronto’s “program resources barely keep pace with cost increases.”

How do Osgoode’s financial aid programs compare?

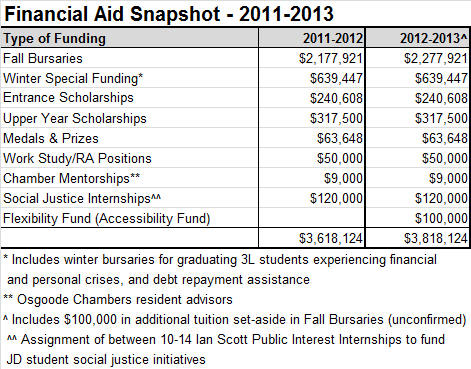

A rough calculation of total available financial aid per student at all four schools, including scholarships, bursaries and awards, shows that there is just under $4,000 available to each Osgoode student. As a percentage of tuition and ancillary fees, this amount is roughly 19.6%, higher than Western and Ottawa, but lower than Toronto. While total financial aid and financial aid per student are not indicative of how much financial support a student would receive from any particular school, these figures are demonstrative of the real cost of legal education.

Osgoode’s financial aid is allocated as follows:

How are Osgoode’s annual budgets set?

Each year, the Office of the Executive Officer provides a 3 year rolling budget to York University’s Vice President, Academic for approval, which includes revenue and expense projections for the following 3 years. Because Osgoode’s tuition levels and enrollment numbers are predictable, Osgoode’s revenues are more predictable than those of other faculties at York where student enrollment and retention fluctuate and vary. In order to accurately determine what Osgoode’s expenses will be and to ensure that the law school does not run a budget deficit, Phyllis meets annually with each department (e.g. Recruitment, Admissions & Career Development, Law Library, etc.) to assess current year spending and predict future needs. Ultimately, Osgoode’s budget and any tuition increases must be approved by York University’s Board of Governors.

Has Osgoode been running budget surpluses or deficits?

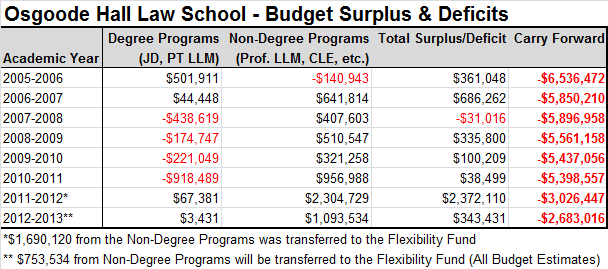

Since at least the 2005-2006 academic year, Osgoode has had a large interest-free debt “carry forward” owed to York University, which accumulated over the years as a result of investments in the law school. While Osgoode’s degree programs (JD, LLM & PhD) are supposed to break even – that is, the law school is only looking to spend the amount of money it takes in – Osgoode ran deficits of $438,619, $174,747, $221,049, and $918,489 between the 2007-2008 and 2010-2011 academic years. During this time, Osgoode’s non-degree programs (programs operated by Osgoode Professional Development) generated sufficient income to offset the deficits.

It was not until 2011-2012 that Osgoode’s degree programs generated a $67,381 surplus that was combined with Osgoode Professional Development’s $2.3 million income. Of this, $1.7 million was transferred to a newly created Flexibility Fund, while future surpluses will be put towards the Flexibility Fund and improve Osgoode Professional Development programs, except annual $343,431 payments to the debt “carry forward,” which should eliminate it within 8 years.

What is the Flexibility Fund?

The Flexibility Fund was established this year in order to advance the law school’s Strategic Plan goals until the end of next year (2013-2014). It also includes a contingency fund to help mitigate any negative future changes to Osgoode’s budget (e.g. York University budget cuts and the new budget model).

The Flexibility Fund includes:

- $200,000 for the newly created Accessibility Fund, including:

- $100,000 for additional in-program bursaries

- $65,000 to match donations to graduation bursary endowments

- $25,000 for adjunct faculty student research assistant support

- $10,000 for two Wendy Babcock bursaries awarded in 2010-2011

- $150,000 for the newly created Experiential Education Fund to expand and enhance experiential learning at Osgoode

- $56,700 was awarded to 14 projects in March 2013, including 3 projects initiated by JD students

- $150,000 for the newly created Research Intensification Fund to help recognize Osgoode as a leading research intensive law school that produces critical and engaged policy

- Funding may be used for faculty grants, graduate student travel, conference initiatives, visiting speakers, investments in the library and equipment

- $890,120 for the newly created Contingency Fund

- $300,000 for Osgoode Professional Development to invest in IT infrastructure in order to maintain a competitive edge in e-learning

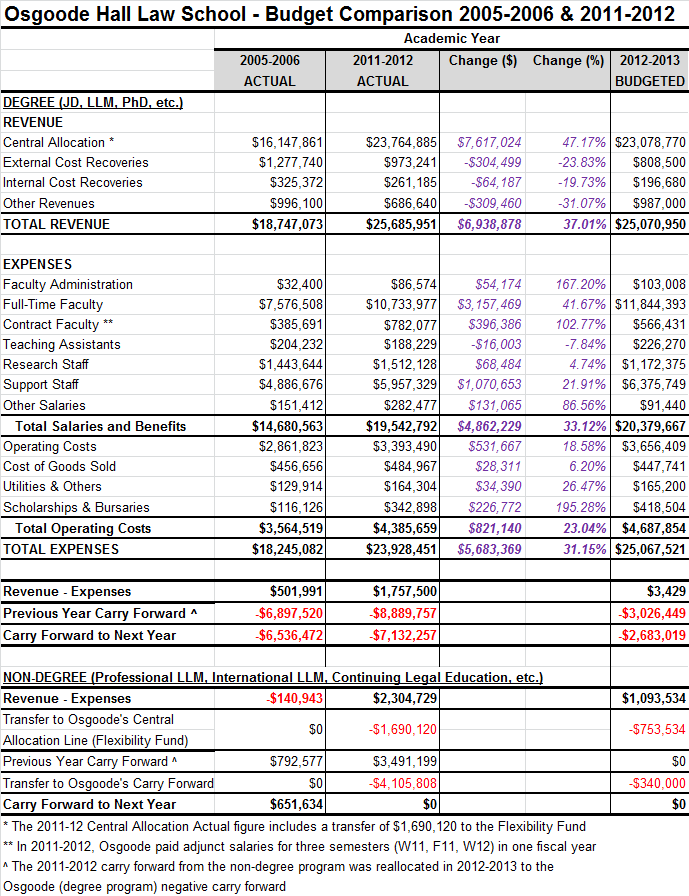

The budget above compares Osgoode’s actual costs and revenues between the 2005-2006 and 2011-2012 academic years. It also shows the estimated budget for this year.

How have Osgoode’s revenues changed over the years?

All JD tuition is paid directly to York University. Under the current York University budget model, Osgoode receives a large, lump sum base allocation and tuition differential from York University’s Central Administration.

The base allocation includes JD tuition and government funding, less a portion retained by Central Administration to pay for certain services (e.g. building utilities and maintenance, payroll and human resources, counselling and disability services, etc.). The tuition differential represents the JD tuition increases each year (less a portion withheld for York University services). Osgoode retains over 90% of the tuition differential. Of the amount transferred to Osgoode, 10% is retained as tuition set-aside bursary funding.

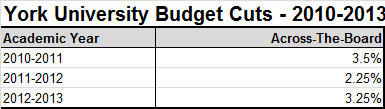

One of the problems with the current budget model is that the base allocation is a historical number and it is not possible to determine exactly how much government funding is received or how much York University withholds for services. Further, due to a University-wide budget deficit, Osgoode’s base allocation was reduced by 3.25% this academic year, one of a series of annual cuts that Osgoode has had to absorb.

Central Allocation

This line item is Osgoode’s largest source of revenue and includes the base allocation and tuition differential. This was the only revenue source that increased between 2005-2006 and 2011-2012. The lower maximum tuition increases and absence of additional government funding in the new provincial tuition framework may reduce this revenue growth going forward. As mentioned, a series of York University budget cuts to the base allocation has put pressure on Osgoode’s revenues, which makes annual increases in tuition even more important to the enhancement of the law school. A sample of “across-the-board” budget cuts is below:

External Cost Recoveries, Internal Cost Recoveries, and Other Revenues

Funds in the External Cost Recoveries category include non-credit course tuition fees, JD material fees, part-time LLM material fees, donations, and photocopying revenue from the library. The nominal amount representing Internal Cost Recoveries include revenues generated from internal Osgoode units for hospitality, work/study, and salaries. Other Revenues encompasses part-time LLM tuition as well as transfers from trusts and endowments.

Endowments are a significant source of revenue used for both bursary funding and operating costs. In fact, it can be seen that $342,898 was spent on scholarships and bursaries in the 2011-2012 academic year alone, an increase of $226,772, or 195.28%, since 2005-2006.

How have Osgoode’s expenses changed over the years?

Osgoode spent $23.9 million to run the law school in the 2011-2012 year. Of this, $19.5 million, or 81.67%, went to salaries and benefits, while the remaining $4.39 million, or 18.33% was spent on operating costs, utilities, scholarships, and bursaries. This analysis will focus on the three largest line items which, together, represented 83.94% of Osgoode’s 2011-2012 expenses: Full-Time Faculty, Support Staff, and Operating Costs.

Full-Time Faculty – $10.7 million

Salaries and benefits representing $10.7 million for full-time faculty (except on sabbatical) was the largest expense to Osgoode in the 2011-2012 year. Since 2005-2006, this cost has increased by $3.16 million, or 41.67%, which works out to an annual growth of 6.0% each year. As a comparison, Canada’s annual inflation rate fluctuated between 1.0% – 2.7% during this period. Osgoode’s full-time faculty formed the Osgoode Hall Faculty Association this year and are currently in negotiations for their first collective agreement. While this will reduce uncertainty by creating a clear and transparent set of arrangements with respect to faculty compensation, benefits, discipline, etc., it is unclear what net affect this will have on aggregate full-time faculty compensation.

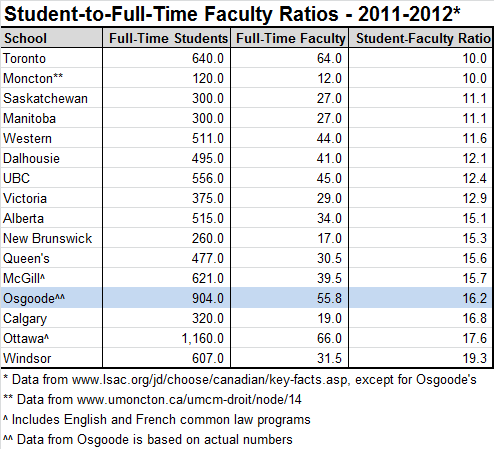

From the data provided by Phyllis, it appears that nearly the entire increase represented increased compensation – not additional full-time faculty members. In 2005-2006, Osgoode had the equivalent of 54.72 full-time faculty. By 2011-2012, this increased to 55.77, a net addition of just 1.05 full time equivalents. This works out to a rise in average compensation per full-time faculty member from $138,460 in 2005-2006 to $192,469 in 2011-2012.

Increased compensation between 2005-2006 and 2011-12, came from annual “across-the-board” salary increases of between 2.5% – 3.5% and “progress-through-the-ranks” increases of between $2,674 – $3,095. The latter increases are annual raises that vary by faculty member and recognize the faculty member’s academic and professional development, a portion of which is merit-based.

To be clear, the number of faculty has increased and decreased over the years. For example, when Dean Sossin arrived at Osgoode in the 2010-2011 academic year, there were about 50 full-time faculty members. Since then, 7 new full-time faculty members have been hired and none have retired. The law school also expects to add 4 new members to its faculty complement by 2013-2014.

It is undeniable that Osgoode is home to some of Canada’s leading legal scholars who produce an extraordinary amount of high quality research. The law school also prides itself on hiring full-time faculty members that are equally strong instructors in the classroom. Further, there is an argument to be made that without salary increases, our faculty would be drawn away to other law schools (or private practice – less likely, but still possible) that are willing to pay more.

Nevertheless, these statistics are alarming, given that Osgoode’s 16.2 student-to-full-time faculty ratio is among the worst for any common law school in Canada. Students may ask – and rightfully so – what value the increasing faculty compensation has provided to students over the last 7 years.

Improving Osgoode’s full-time faculty complement is a significant goal, and features prominently in Osgoode’s 2011-2016 Strategic Plan. For example, the fact that we will be adding 4 new full-time faculty members for 2013-2014 is a perfect example of our increasing tuition dollars at work. Dean Sossin notes, however, that to focus on the student-to-faculty ratio overlooks Osgoode’s rich and varied adjunct faculty, new initiatives that feature visiting professors which enhance the curriculum (e.g. McMurtry Visiting Clinical Fellowships) and the law school’s rich experiential education programs, many of which are led by non full-time faculty and which are essential to the Osgoode student experience. Adjunct faculty, contract faculty and visiting professors are also supported by operating funds (which are discussed below) and, in part, tuition. A singular focus also fails to consider the very high quality of Osgoode’s full-time faculty complement and the constant competition between law schools for Canada’s top academic talent.

That said, why is it the case that, notwithstanding consistent tuition increases, Osgoode’s faculty complement has not significantly moved beyond 2005 levels? According to Dean Sossin, there are many factors at work to explain this number – budget cuts (discussed above), unexpected faculty departures (in 2009-2010, for example, both Professor Ben Richardson and Professor Les Green left Osgoode for other law schools) and the decision of the Faculty to hire senior, lateral faculty at higher salaries than entry level faculty all help explain the numbers. Further, Dean Sossin indicated that budgetary pressures prior to his appointment resulted in at least one instance (namely, in 2008-2009) where faculty appointments were cancelled due to a hiring freeze at York University.

Support Staff – $6.0 million

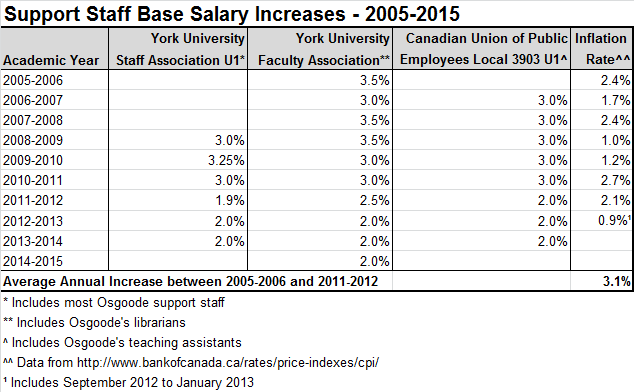

The next largest line item relates to salaries and benefits of support staff, totalling just under $6.0 million in 2011-2012. This category includes student services staff, administrative assistants, librarians, teacher’s assistants and other professional or managerial staff. Costs in this category increased $1.07 million between 2005-2006 and 2011-2012, an increase of 21.91%, which works out to an annual growth of 3.1% each year. According to Phyllis, most of this increase was due to small annual increases in salaries as negotiated in various collective bargaining agreements. A selection of such increases is below:

Like Osgoode’s full-time faculty, the law school would not be the institution it is today without the extraordinary work of support staff, many of whom work in the office block outside the direct sight line of students. Further, the average annual increase of 3.1% during this period more closely tracks Canada’s annual inflation rate, and, in any case, it is unlikely that growth in this line item can be reduced, since most support staff salary increases are negotiated through binding collective bargaining agreements.

Operating Costs – $3.4 million

The last major line item is operating costs, representing $3.4 million of Osgoode’s total spending in 2011-2012. Between 2005-2006 and 2011-2012, operating costs increased $531,667, or 18.58%. The breakdown of costs for each operating expense was not provided by the Office of the Executive Officer, so a more detailed analysis of where operating funds are spent was not possible.

In a general sense, operating costs are – not surprisingly – those expenditures critical to the daily functioning of the law school, including, but not limited to: furniture, office supplies, photocopiers, postage, library books, and select grants to students. Funds are also spent enhancing the academic and student experience, including improvements to experiential education and student wellness.

The operating budget does not include Osgoode’s capital spending, including the $55 million invested into the new Ignat Kaneff Building, which is extraordinarily valuable to students and reduces on-going operational and maintenance costs due to the efficiency of the new building.

How will the situation change going forward?

Assuming the same level of spending growth as in the last 7 years, no additional government funding, and assuming that Osgoode receives the same percentage of tuition increases every year, the law school needs to increase tuition by the previous maximum of 8%/4%/4% each year just to break even.

The new provincial tuition framework released on March 28, 2013 has reduced the annual maximum professional program tuition increase to 5% per year – with no additional government funding – which means that the law school will need to decrease spending or risk running budget deficits.

A transition to York University’s new activity-based budgeting model may decrease the law school’s revenue by forcing Osgoode to pay more for central York University services. Instead of Osgoode receiving a base allocation and a portion of the tuition differential, the law school will receive all revenues directly (e.g. tuition and government subsidies) and be responsible for remitting a portion back to York University for shared central services (e.g. building utilities and maintenance). This will increase transparency and create efficiencies by holding each University department to account for all revenue and spending, but may require Osgoode to pay twice for certain services. The Dean is currently negotiating with York University to determine what services, if any, Osgoode will be able to “carve out” of payments back to the University, since the law school operates many departments which York University considers duplicate services (e.g. student services and the career development office), despite their tailored nature to the law school environment. Without these “carve outs,” Osgoode may be in the unenviable situation of needing to pay for both services, further increasing pressure on Osgoode’s budget.

Concluding Thoughts: How do we move forward from here?

Without a doubt, the issue of law school tuition is complex. It is in the interests of Osgoode’s stakeholders to increase transparency in the tuition-setting process, as this allows students to better assess value for money. To enhance the value of an Osgoode legal education, it is necessary to make investments in the law school – but what is the “right” level of investment? Further, an individual’s conception of the “right” amount of tuition is also informed by their belief as to what proportion of funding must come from public and private sources. In other words, to what extent should law students – and the communities they will be serving – be responsible for paying for the value received from a legal education?

To move forward, it is imperative that the law school’s administration evaluates spending levels in light of their commitment to accessibility and social justice. Of course, it would be incorrect to assert that Osgoode’s faculty and administration do not consider accessibility and social justice to be extraordinarily important. In fact, Dean Sossin pointed out that the law school has made many strides in this regard, including matching donations to the Wendy Babcock Bursary Fund through the $200,000 Accessibility Fund (part of the $1.7 million Flexibility Fund) and a new fund in honour of John Plater for a bursary related to health law. Nonetheless, uncertainty surrounding York University’s new budget model, future York University budget cuts, and the province’s now-expired tuition framework are all significant pressures on the budget. Unlike other faculties at the University, Osgoode is unable to increase revenue through enrollment growth. Further, this analysis must be conducted within the current day environment where articling positions are increasingly scarce (due in part to increasing demand from offshore graduates and increasing enrollment in other Ontario law schools), an untested Law Practice Program is being rolled out for those without articling placements, and salaries for newly called lawyers are in decline despite the rising debt levels of the new calls (see Canadian Lawyer Magazine’s “2012 Canadian Lawyer Compensation Survey” by Heather Gardiner).

More research should also be conducted to determine how various levels of government can more effectively support legal education. Whether this is through increased direct funding, re-introduction of some form of matching program to grow University financial aid endowments, or perhaps income-linked post-graduation debt relief, law students need a stronger voice at the table. Limiting tuition increases to a maximum of 5% per year is an improvement, but more can be done. The Law Students’ Society of Ontario, of which Osgoode’s Student Government is now a member, may assist on this front.

Other questions that may be explored include:

- How will York University’s new budget model affect Osgoode’s operating budget?

- What value do Osgoode students receive from the ancillary fees paid directly to York University (e.g. currently $890.68 per academic year) and how are fees changing?

- What other fees do Osgoode students pay (e.g. ExamSoft fees, course packs in light of fair dealing provisions for educational institutions) and how are they changing?

- In what way does tuition from de-regulated (and substantially higher) JD tuition subsidise Osgoode’s LLM and PhD programs (e.g. through teaching credit to full-time faculty)?

- How can Osgoode continue to leverage external funding partnerships (e.g. Osgoode’s new Business Law Internships with McCarthy Tétrault LLP and the Winkler Institute for Dispute Resolution and the Winkler Chair in Dispute Resolution)?

- How can Osgoode continue to improve JD student research opportunities (e.g. utilizing the Research Intensification Fund and the new research disseminating Digital Commons)?

Irrespective of the challenges, there are ways to move forward. Your Student Caucus is committed to addressing the issue of rising tuition and we look forward to working with other members of the Osgoode community during the summer and in the coming year.

With contributions by Tom Wilson (Student Caucus Chair, 2011-2012), Jeff Mitchell (Student Caucus Chair, 2012-2013), Dean Sossin, and Phyllis Lepore Babcock (Executive Officer).