Reflections on the Impending Strike at York

York University and CUPE 3903 are moving closer and closer to both a deal and an impasse. The pursuit of one entails the advance of its opposite. From this paradox emerges the absolute uncertainty of the whole situation, a source of great anxiety and, for some, great exhilaration too. On Monday, March 2nd, members of the union will vote on the administration’s final offer, by all accounts the most compelling it has made to date. Although the exact terms have not been disclosed at the time of writing, three major points will likely remain contentious:

- Job security for contract faculty, many of whom regularly receive offers of employment as little as two weeks before the start of classes

- Bursary assistance for international graduate students, whose average tuition fees went up by 50% (approximately $6000) in 2014

- Across-the-board wage increases, which the administration is seeking to fix at 1% per year, well below the rate of inflation

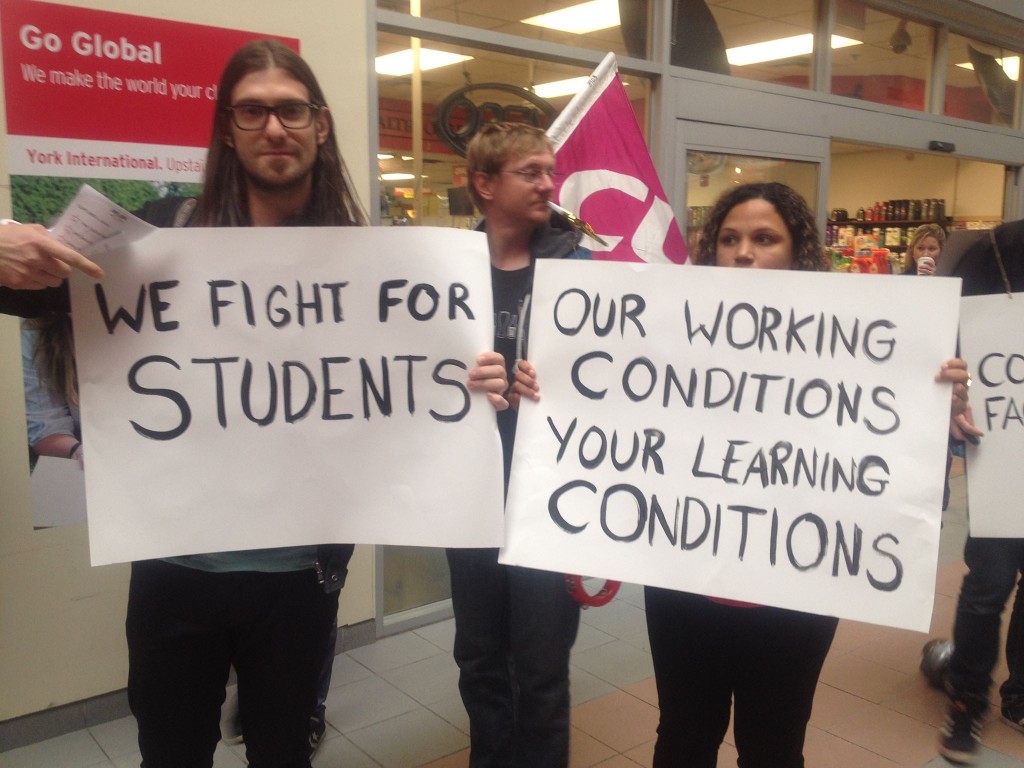

If a majority of the TAs, GAs, and contract faculty who comprise CUPE 3903 reject the administration’s final offer at their general membership meeting on Monday evening, the union will proceed with strike action the following morning. Picket lines will form, classes, tutorials, and labs will be suspended, and 51,000 York undergrads, including a pinch of Osgoode students, will be forced to reckon with the collective assertion of that essential yet devalued precondition of their education – labour. Or, to put it in the union’s terms, “the university works because we do.”

So why stop working then? That is the question most undergrads will be wrestling with come Tuesday. How it gets answered will not only affect the way students make sense of the strike, but will also influence the positions they take with regard to it, thereby shaping the strike’s outcome.

Rather than propose an answer, however, I want to move upstream from the actual negotiations to focus on something particularly significant to future practitioners of law. Namely, that education workers at York possess a legal right to strike.

Indeed, contrary to recent government conduct, strikes are not prohibited in any province or territory in Canada, certainly not when they are fully contemplated as part of a months-long collective bargaining process like the one now coming to a close at York.

According to scholars Judy Fudge and Eric Tucker, strikes are more than just permissible: they constitute “a social practice that is deeply embedded in Canadian society.” Long before 1872, the year “it became clear that striking itself was not illegal” in Canada, workers frequently withdrew their labour power in disputes with all sorts of different employers. They continued to do so thereafter in the form of in economic sanctions as well as expressions of political protest – practices, in other words, of freedom.

Over the course of the early twentieth century, things began to change. Proliferating workplace legislation deliberately limited the possibility of spontaneous strikes while simultaneously conferring upon workers a set of more narrowly-defined rights of work stoppage. The decisive moment came after World War II, when the expansive “freedom to strike” was finally supplanted by a more restrictive, legally-mediated “right to strike,” consecrated in the so-called Wagner Act model of collective bargaining. Notwithstanding the weight of these shifts, the history traced by Fudge and Tucker attests to the endurance of the practice of work refusal itself. Striking, in one form or another, was the constant in an otherwise variable and tumultuous period of social, economic, and political transformations.

Such persistence is of course no cause for celebration. Rather, the ongoing role of the strike in labour disputes reflects both the fundamental condition of inequality under which work was and is performed in Canadian society, and the central means workers have of tipping back the scales in their favour. Here is how an unlikely commentator described the dynamic half a century ago:

In the present state of society, in fact, it is the possibility of the strike which enables workers to negotiate with their employers on terms of approximate equality….If the right to strike is suppressed, or seriously limited, the trade union movement becomes nothing more than one institution among many in the service of capitalism: a convenient organization for disciplining the workers, occupying their leisure time, and ensuring their profitability for business.

So wrote Pierre Trudeau, then an aspiring journalist covering the pitched Asbestos Strike of 1949.

And so, it seems, the Supreme Court of Canada just concurred. Writing for the majority in Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v Saskatchewan, 2015 SCC 4, Abella J echoed Trudeau’s line of reasoning:

In their dissent, my colleagues suggest that s.2(d) [of the Charter] should not protect strike activity as part of a right to a meaningful process of collective bargaining because “true workplace justice looks at the interests of all implicated parties,” including employers. In essentially attributing equivalence between the power of employees and employers, this reasoning, with respect, turns labour relations on its head, and ignores the fundamental power imbalance which the entire history of modern labour legislation has been scrupulously devoted to rectifying…. [Although s]trike activity itself does not guarantee that a labour dispute will be resolved in any particular manner, or that it will be resolved at all….what it does permit is the employees’ ability to engage in negotiations with an employer on a more equal footing.

Recognizing the right to strike as an “indispensable component” of the Charter-protected right to collective bargaining, Abella J proceeded to grant “constitutional benediction” to its exercise. Admittedly, Saskatchewan Federation of Labour is only a month-old decision, and so still in the early stages of jurisprudential gestation. But it is difficult to read Abella J’s judgment, amplified as it is by the zealous, fitful dissent of Rothstein and Wagner JJ, without believing that something consequential has just come to pass.

And not a moment too soon, either.

To understand the impending strike at York across a longer historical arc, capped by uncharacteristically sage judicial commentary, is thus to better appreciate the function and meaning of CUPE 3903’s collective refusal to work.

As students of law, prospective officers of the court, and ongoing beneficiaries of union members’ labour, there is ample onus on us to support this strike in principle, as the exercise of a right vested by the law we swear to uphold.

Fortunately, CUPE 3903 members won’t be holding their breath – no one in the pursuit of freedom has ever had that luxury.