A Topic of Access to Justice for the Mentally Ill

What makes a mental illness? While the phrase is bounced around quite often, defining the boundaries and understanding the diversity of psychiatric disorders is a very challenging task. Part of this can be attributed to the dynamic nature of psychiatric discovery. While the volume of scientific literature is constantly growing and what constitutes a particular condition may be changed or redefined in its entirety, how can one expect those outside of the field to know of its exact nature and understand the appropriate accommodations? Of course, this is why we have professionals with specialized knowledge of the human psyche, but what about situations where the fate of peoples’ psychological conditions is entrusted to those without the requisite knowledge?

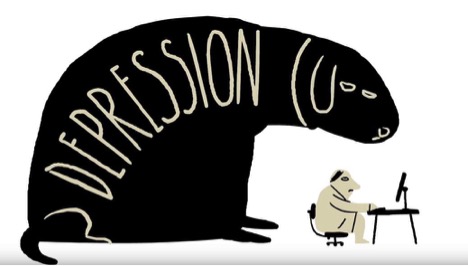

While it may be easy to visualize a barrier to justice for someone with a physical condition, conceptualizing the barriers for a mental condition requires another degree of abstraction and understanding. For example, in practice a lawyer may view an individual afflicted by major depressive disorder (MDD or, more commonly, depression) as someone experiencing a bout of sadness that extends over a longer duration. While some elements of this view may be correct, it fails to capture the debilitating nature of mental illnesses or their scientific underpinnings.

A loss of interest in self preservation (a common feature of depression) may create elusive barriers to the pursuit of legal counsel. There may be clear evidence of a legal violation–say violent domestic abuse–but depression has a peculiar way of dissuading people from pursuing what may otherwise appear to be an appropriate course of action. Continuing with our example of MDD, being bombarded by thoughts of worthlessness or that “I deserved it” can create a seemingly rational argument for not pursuing justice for the affected person. When gripped by depression, it may seem wholly rational to do nothing and bear the burden of the wrong. Furthermore, should the afflicted individual seek counsel, the lawyer may not accurately consider how a long and strenuous legal conflict may exacerbate her/his client’s well-being. So, it becomes apparent that lawyers must have some understanding of the nature of the client’s illness, but how deep should this rabbit hole go?

Say we pose a slightly different situation–not only is the client affected by depression, but also a generalized anxiety disorder. As with depression, the presence of severe anxiety may reduce the likelihood of an afflicted person pursuing legal and psychiatric counsel when needed. Thus, adding an anxiety disorder to the mix would further decrease the chances of successfully accessing the appropriate legal resources while also increasing the chances of severe risk factors, such as suicide. While the choice of adding an anxiety disorder to our hypothetical client may appear to be a mere coincidence, depression and anxiety are actually common comorbidities. That is, they are illnesses that are likely to occur together due to their biochemical underpinnings. So, the hypothetical introduced so far is not an extreme irregularity in the field, but a rather probable occurrence that perhaps has been given insufficient attention in practice.

In consultation, the willingness to communicate the details of one’s case to counsel or participate in high pressure meetings that are billed at a rate of $500 per hour is an additional burden on the mentally ill. Keep in mind, the pursuit of legal counsel may also have been stimulated by an exceptionally bad manifestation of some stimulus–say a very damaging domestic abuse event–and this creates a high stress environment for the prospective client. To add to that, those afflicted by mental illness may be underemployed or subject to abusive or discriminatory employment practices which would further inhibit the ability to meet a lawyer’s high fees. Imagine the combined effects of the low mood and low energy of depression with the persistent tension of anxiety and being faced with the choice of whether to spend the last of one’s savings on talking to a lawyer–who may know little to nothing about your traumas–in hopes of ensuring the especially devastating abuse suffered at the hands of your partner or relative ceases. With this in mind, describing the affected person as merely chronically sad and nervous is quite the understatement.

So, how can the legal community hope to address the special needs of people with mental illnesses? There are two main approaches to addressing these needs: greater interdisciplinary collaboration with mental health specialists and educating lawyers about rudimentary mental health issues. For the former, liaising with physicians and psychologists as well as being able to understand the idiosyncratic characteristics of one’s client and how best to approach her/him to make legal consultations as comfortable and as nonstrenuous as possible could help close the gaps in communication. In the case of the latter, having a general familiarity with the nature of psychiatric conditions and what they entail would grant some much-needed context to the position of one’s clients, what they might hope to achieve through legal counsel, and how the law can improve their overall standard of living.

At the core of access to justice for the people with mental illness is the need for an empathetic approach in legal practice and understanding that barriers to justice can manifest in many ways. While the legal community is not directly responsible for their clients’ mental health it would be in their best interest in practice to understand what sort of actions and attitudes will help make consultations and proceedings as accommodating as possible without adding unnecessary stress. In the end, the issues faced by the mentally ill when dealing with the law represent another area of nonlegal knowledge which must be incorporated into legal practice to maintain equality for all persons.

This article was written by Dominic Cerilli, who received his MSc in Chemical Sciences and HBSc in Biochemistry from Laurentian University and is currently affiliated with the Health Law Association (HLA), the Osgoode Mental Health Law Society (OMHLS), the Osgoode Peer Support Centre (OPSC), IPOsgoode, and the Law in Action Within Schools Program (LAWS).

This article is part of the Osgoode Health Law Association’s Perspectives in Health column. Keep up to date with the HLA on Facebook (Osgoode Health Law Association, Osgoode Health Law Association Forum) and Twitter (@OsgoodeHLA).