The Overuse of Segregation and the Interplay Between Mental Health and Segregation

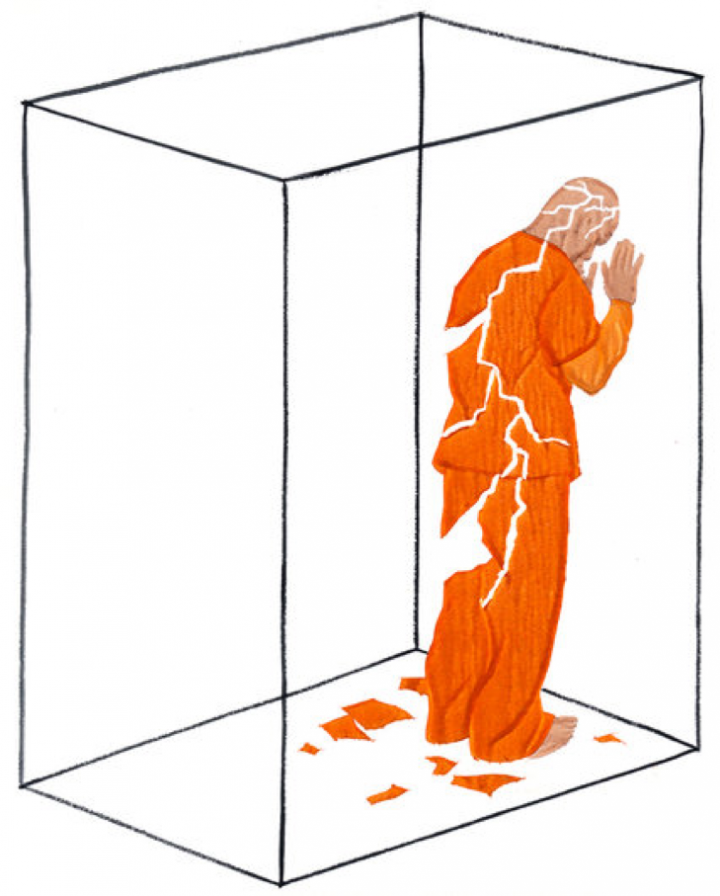

1,560. That is how many days 23-year-old Ontario inmate, Adam Capay, spent in continuous segregation, without trial, in a small, Plexiglas-lined cell.[i] The UN Commission on Human Rights defines prolonged segregation as anything greater than fifteen days. If the segregation exceeds fifteen days, the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners designates the treatment as torture.[ii] According to the Mandela Rules, the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services (MCSCS) is engaged in torturous practices in Ontario. A guard working at Mr. Capay’s prison revealed this instance of the gross misuse of segregation, but this horrific story is merely the tip of the iceberg.

1,594 of the 4,178 prisoners placed in segregation during a two-month period in Ontario reported mental health concerns. Only 4.3% of these inmates were in segregation for disciplinary reasons. The other 95.7% were placed in segregation, twenty-three hours of isolation, increased surveillance, twenty-four hours of artificial light, and minimal stimulation, for administrative reasons.[iii] In other words, MCSCS has no other way to rectify some issues than to throw a human being into torturous conditions, often for their “protection.” The John Howard Society recently published a report on the healthcare system in Ontario prisons, noting the disproportionate number of chronic and acute conditions experienced by prisoners who are under-served “…by a parallel, yet unequal system.”[iv] Placing prisoners in segregation drastically reduces their access to badly-needed mental health services that are already limited.

62% of women and 50% men require further mental health check-ups upon admission to Canada’s prisons.[v] Notably, segregation can not only exacerbate existing mental illnesses, but can even evoke mental illness in those without previous mental health issues.[vi] Dr. Grassian, through his solitary confinement research in American prisons, found that “even a few days of solitary confinement will predictably shift the electroencephalogram (EEG) pattern, [a neural brainwave measurement], toward an abnormal pattern characteristic of stupor and delirium.”[vii] If it only takes a few days to elicit this response, one can only speculate on the effects of 1,560 days.

Subjecting prisoners to these conditions is inexcusable. The crimes or alleged crimes these individuals committed before their incarceration are irrelevant to the treatment they are receiving. The government condemns torture abroad, yet it is complacent to torture on Canadian soil. Outside of short-term periods to protect other inmates, there is simply no justification for placing a prisoner in segregation. Our justice system remains largely unmoved in remedying this issue.

Perhaps the liberty of inmates is of no importance in this country. Yes, these people committed crimes, with the result of significant restrictions on the individual’s liberty. But to what extent do we allow his or her liberty to be restricted? Can we justify placing someone with mental health issues in segregation indefinitely, simply because the system is incapable of dealing with mental health issues? This consequence is absurd.

Several groups—including the John Howard Society, the Elizabeth Fry Society, and the Ontario Human Rights Commission—have made significant positive changes in Canada’s prison system through their investigations. But wholesale change is badly needed. Defense lawyer Michael Spratt expressed it best in his podcast when he suggested that the system is not broken; the system works exactly as designed, and that is the problem.[viii]

Prison systems in Scandinavia take an entirely different and humane approach to incarceration, and have recidivism rates significantly lower than those in Canada.[ix] Mass killer, Anders Brevik, was subjected to Norway’s version of segregation, which included family visits, a PlayStation, a computer, a private bathroom, and a treadmill.[x] Mr. Capay, who was only in jail for a minor property offence and not yet convicted of murder, was subjected to our horrific segregation conditions.

The homogenous population in Scandinavian countries does make the process of implementing programs to reduce these rates much easier, but this does not excuse Canada from working on similar initiatives. To start, the physical design limits that force MCSCS to turn to segregation cells needs to be addressed. This change will allow Canadian prisons to stop using segregation cells for administrative reasons. Additionally, MCSCS needs to become aware of the extensive mental health detriments that accompany segregation, as the consequences only lead to increased use of segregation and difficulties in the system.

The words of Kate Richards O’Hare, from her book, In Prison, in 1923 remain true today: “…by the workings of the prison system, society commits every crime against the criminal that the criminal is charged with committing against society.”[xi] In Canada’s case, an often worse crime.

Nathan Jones, 1L

This article was published as part of the Osgoode chapter of Canadian Lawyers for International Human Rights (CLAIHR) media series, which aims to promote an awareness of international human rights issues.

Our website: http://claihr-osgoode.weebly.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/claihrosgoode

[i] “Ontario’s Sickening Treatment of Adam Capay,” Editorial, The Globe and Mail (24 October 2016) <www.theglobeandmail.com>.

[ii] The United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, UNODCOR, 2015, A/RES/70/175 [Mandela Rules]. Rules 1, 43, and 44 are particularly significant:

Rule 1

…No prisoner shall be subjected to, and all prisoners shall be protected from, torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, for which no circumstances whatsoever may be invoked as a justification.

Rule 43

In no circumstances may restrictions or disciplinary sanctions amount to torture … The following practices, in particular, shall be prohibited: (a) Indefinite solitary confinement; (b) Prolonged solitary confinement; (c) Placement of a prisoner in a dark or constantly lit cell [emphasis added];

Rule 44

…[segregation] shall refer to the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact. Prolonged solitary confinement shall refer to solitary confinement for a time period in excess of 15 consecutive days.

[iii]Supplementary Submission of the Ontario Human Rights Commission to the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services’ Provincial Segregation Review (Toronto: Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2016) at 9.

[iv] John Howard Society of Ontario, “Fractured Care: Public Health Opportunities in Ontario’s Correctional Institutes,” (Toronto: 2016) at 6.

[v] Correction Service of Canada, “Research Results, Mental Health,” (Ottawa: 2014).

[vi] Stuart Grassian, “Psychiatric Effects of Solitary Confinement” (2006) 22 Wash UJL & Pol’y 325.

[vii] Ibid

[viii] Michael Spratt & Emelie Taman, “A New Judge, Racist Police, and Solitary Confinement”, (3 Nov 2016), The Docket, online: <www.michaelspratt.com/poadcast-legal-matters> at 53:00.

[ix] Public Safety Canada, “The Recidivism of Federal Offenders”, (Ottawa: July 2003); Seena Fazel & Achim Wolf, “A Systematic Review of Criminal Recidivism Rates Worldwide: Current Difficulties and Recommendations for Best Practice”(2015) 10:6 PLoS One at e0130390; Carolyn W Deady, “Incarceration and Recidivism: Lessons from Abroad” (2014).

[x] Kjetil Malkenes Hovland, “Norway Violates Mass Murder Anders Brevik’s Human Rights, Judge Rules” The Wall Street Journal (20 April 2016), < www.wsj.com>.

[xi] Kate R O’Hare, In Prison (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2015); Doran Larson, The Atlantic, “Why Scandinavian Prisons Are Superior”, (24 September 2013), <www.theatlantic.com>.