As we enter into Mental Health Awareness Week, I can’t help but observe that, while well-intentioned, it does nothing to solve the underlying problems law students face when it comes to combatting stress and anxiety, and optimizing their learning. How could it? But if this is all the institution we pay tens of thousands of dollars to each year can muster up, it leaves me feeling uneasy that our solid legal education isn’t as solid as we think.

Of the several articling students and lawyers I’ve spoken with, the first thing that they will tell you, emphatically, is that law school doesn’t prepare you for legal practice. Then what does law school prepare us for? The Bar? Well, no: the topics covered on the exam are not mandatory courses; as a standardized test, it has its own study system. If the answer is to learn about the law and hone our critical thinking skills towards legal issues (and why not, it is a school, after all), is it really meeting our expectations? I don’t think so. And it has nothing to do with the quality of our professors, the boundless opportunities the administration provides us with or the community the students strive to make as wonderful as it is.

The problem is one of misplaced goals. It is the same problem that plagues most levels of education. The focus is on generating candidates for the next steps of the greater process; not on ensuring that learning students take part in preparing themselves for it. For example, in the United States, the No Child Left Behind Act is premised on setting higher standards and establishing measureable goals: to improve outcomes, not learning, and incentives are designed around meeting those standards. This doesn’t seem to make sense, especially when considering that positive outcomes flow naturally from improving learning. Transposing this idea onto law school, it is not too difficult to see that the system is designed in the same way. Law school does not care if exams or long papers measure how well one knows the law. It does not care that it fails to emulate how our knowledge will be applied in practice. The grading system exists solely to rank students and position them for the next step in the process. To change that requires a leap of faith—a revolution—to remedy an institutional problem that those in power are too afraid to take.

With all the current research in psychology, it is disheartening to observe that few of the insights gained from study after study aren’t implemented into greater society; education is no different. Implementing positive and educational psychology (both growing fields producing a lot of interesting research) into the law school curriculum can go a long way into making the experience far better.

Let’s start with mental health. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) programs have been around for over thirty years and the science behind mindfulness training has received significant support for fostering self-care, reducing stress and serving as a catalyst for positive growth and development. For an experience as stressful as law school, why isn’t the approximately eight week, $300/per person program (not too steep a price considering tuition was over $20 000 this year) something the administration makes available and mandatory for its students to complete? It will make us better professionals and allow us to productively manage the educational challenges we face.

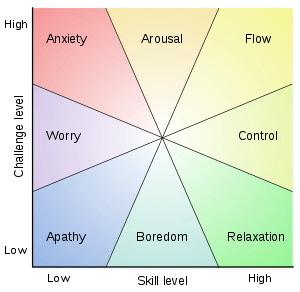

Now that students are better equipped to handle the overwhelming nature of law school, the next step would be figuring out how to immerse students in their work. In that regard, there is a helpful concept in positive psychology called “flow”. Colloquially, it is known as: being in the moment; in the zone; on fire; etc. Flow is a mental state of complete absorption in an activity and motivation is directed, in totality, to it.

What bars this positive experience and perfect alignment of pleasure in work? Boredom and anxiety—feelings that too often overtake us. How do we enter into flow? When we are challenged to actively apply our knowledge and skills.

According to the flow model, mental state correpsonds to challenge level and skill level.

Flow theory postulates three conditions for achieving this state:

- Involvement in an activity with clear set goals and progress (provides direction and structure)

- The activity gives clear and immediate feedback (helps people negotiate changing demands and adjust performance)

MICHAEL CAPITANO, Staff Writer