ISIS Edition

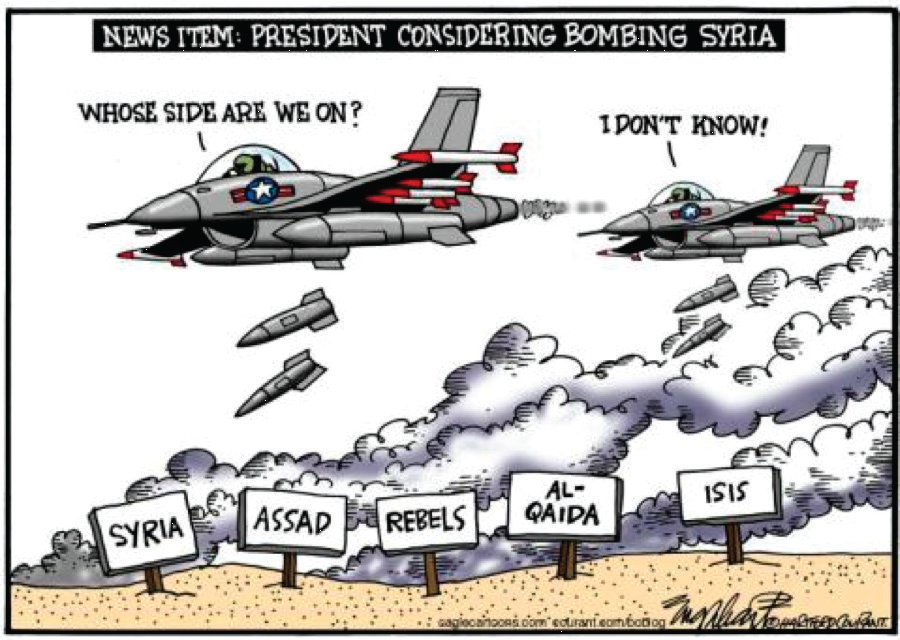

Last month, President Obama laid out his plan to combat the Islamic State (referred to as both ISIS and ISIL) with air strikes in Iraq and Syria. Canada and the United Kingdom have both decided to join the US-led campaign targeting ISIS in Iraq. However, legal scholars have been mixed on whether this bombing campaign is considered legal under international and US domestic laws. How important is the law in seeking to regulate international actors?

Under international law, Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter prohibits the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. There are two notable exceptions to this foundational rule. First, a UN Security Council resolution can authorize the use of armed force under a Chapter VII mandate. Second, Article 51 of the UN Charter, as well as customary international law, have recognized that states have the right to resort to collective or individual self-defence in response to an armed attack.

It is clear that the US-led coalition does not have a Security Council resolution authorizing the use of force in Iraq or Syria, and it is doubtful that the coalition will try and obtain one given the likelihood of a Russian veto. Russia, a permanent member of the Security Council, has supported the Assad regime for the past three years, and is unambiguously against the use of force by the West in Syria.

In the absence of Security Council approval, can the US justify the strikes against ISIS inside Iraq and Syria within the confines of self-defence? According to Article 20 of the International Law Commission’s (ILC) Articles on State Responsibility: “Valid consent by a State to the commission of a given act by another State precludes the wrongfulness of that act in relation to the former State to the extent that the act remains within the limits of that consent.” As such, international law permits the Iraqi government to invite a foreign power into its territory to help remove non-state actors that pose a threat.

The legal justifications for strikes within Syria are more complex and ambiguous. The US Ambassador to the UN, Samantha Power, has argued that strikes within Syria are considered legal on two grounds: first, it is maintained that because ISIS poses an imminent threat to Iraq, and because ISIS is primarily based in Syria, under Article 51 of the UN Charter, Iraq has a right to act in self-defence. Second, because Syria is “unable or unwilling” to combat ISIS within its own territory, Iraq is entitled to intervene without the consent of the Syrian government.

However, the “unable or unwilling” standard is not yet accepted as a solidified doctrine in international law. International legal scholar Martti Koskenniemi points out in his book From Apology to Utopia that due to the radical indeterminacy of international law, there is no objective position the law can defend. Therefore, rather than viewing international law as a panacea for complicated political problems, the important question to ask when assessing the benefits or disadvantages of the use of force is not whether to go by the law, but, as Koskenniemi asserts, by “which law or whose law” (xiv). While international law is necessarily an evolving realm, it is crucial to ask how the law is being shaped to benefit some actors over others.

It is important to also assess how the United States is justifying the military campaign against ISIS under the country’s domestic laws. President Obama is relying on the Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF) resolution to validate the strikes as legal under US domestic law. The AUMF was originally passed by Congress in 2001 in order to conduct military operations against those who “planned, authorized, committed, or aided” in the attacks on September 11, 2001. It has now been expanded beyond its original mandate as a justification to fight a new threat.

President Obama told the Boston Globe in 2008 that “The President does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation.” Is the threat posed by ISIS considered an imminent threat to the US? Journalist Glenn Greenwald of The Intercept, has recently written, in a piece entitled “The Fake Terror Threat Used to Justify Bombing in Syria,” that US officials have failed to prove that ISIS poses an imminent threat to US soil. According to Greenwald, the US is claiming that “the Khorasan Group,” which has been targeted by air strikes in Syria, is an imminent threat insofar as they are planning to use explosives on American and European airlines, and are plotting against a US homeland target. However, there has been no evidence given by the American government to support any of these claims.

Can the AUMF doctrine be constantly expanded to target endless wars against whoever the US decides it wishes to fight next? While international and domestic laws are important as a way to respond to international relations, it is important, I think, to follow Koskenniemi and deconstruct how laws seek to legitimise the subjective political positions of international actors. If we don’t, international and domestic laws may be wrangled into serving the geopolitical agendas of the most powerful actors.