Spying, Sports, Showbiz – The “Dark Side” of Modern Society

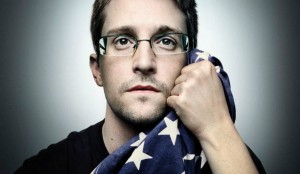

Citizenfour (2014) 3/4

Urgent, fascinating, and tastefully designed, Citizenfour is a primal political fable for the digital age; prosaic in its presentation, profound in its details, and perturbing in its implications. Alarming and essential, it’s a tapestry of escalating suspense; a masterful fusion of journalism and art; a rare, remarkably intimate look at a crucial historical event as it happened; a living document of a global scandal straight from the mouth of the whistleblower.

In June 2013, director Laura Poitras (My Country, My Country, The Oath) – recipient of the 2012 MacArthur Genius Fellowship and co-recipient of the 2014 Pulizer Prize for Public Service – became the first journalist contacted by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden. After a series of encrypted e-mails, Poitras travels with Guardian reporter Glenn Greenwald to Hong Kong for the first of many meetings to discuss the strategic release of voluminous evidence of industrial-scale surveillance that will result in the biggest intelligence leak in history.

As Poitras’ third film, Citizenfour is the culmination of a post-9/11 trilogy that spans a dark horizon from Iraq to Guantánamo. It’s a wow of a thriller; an enthralling, thought-provoking tale torn from recent headlines; and a compelling work of cinema, with all the paranoid density and abrupt changes of scenery of a John le Carré novel and a soul that isn’t computer generated. This is bold, fearless filmmaking, with more in common with All the President’s Men and The Conversation than any modern “true narrative.”

Blending the brisk globetrotting of the Bourne trilogy with the atmospheric effects of a Japanese horror film, Poitras adapts the cold language of data encryption to recount a dramatic saga of abuse of power, and demonstrates that information is a weapon that can cut both ways. It’s likely that her storytelling will be overshadowed by her opportunity, her craft by her access, and her thoroughly, unashamedly partisan attitude towards Snowden is an easy target. But she succeeds brilliantly in evoking a shadow villain intent on world domination.

Like a 1970s paranoia thriller with real-world consequences, Citizenfour is a useful primer in the civil liberties and consent issues that Snowden’s disclosures raised. It’s a real-time tableau of the confrontation between the individual and the state; a gripping record of how our rulers are addicted to gaining more and more power and control over us, if we let them. Dictatorships have always relied on the massive gathering of information in order to control their populations; in this brave new cyber world – a Huxleyan or Orwellian dystopia – democracies may similarly be crossing the line. Senators lie and congressmen squirm, and nobody is held accountable except Snowden.

Citizenfour wears many hats: it’s a bombshell revelation, a character study, a world-girdling espionage thriller, a crucial social document, an oblique manifesto, an expertly crafted exposé, and a model of understatement. It may be the most disturbing political documentary since Alex Gibney’s Oscar-winning Taxi to the Dark Side. Its very existence makes us feel the danger of government invasion, yet it stands as a testament to the fact that while cowering under the corporate jackboot, we still have the power of expression, and that’s all we need to get a resistance off the ground.

If Citizenfour ends abruptly, it’s only because the real-life story is still far from over. How often do you watch someone change the world in real time? Big Brother is back, and he’s gone digital. Anyone with a phone should see it.

Foxcatcher (2014) 3/4 Glacial, passive, and modulated, Foxcatcher is a sinuous, swirling, smoke-black parable of toxic mentorism; a stunted and fiercely unhappy piece of work, straining hard to deliver home truths about a commonweal that has beaten itself out of shape.

Wrestler Mark Schulz is invited by multimillionaire heir John du Pont to move onto his wealthy estate and train at his state-of-the-art facility for the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul. Flattered by the attention, Mark jumps at the opportunity, hoping to step out of the shadow of his revered brother, Dave, who takes on the role of coach, despite his nagging uncertainty of du Pont as eccentric benefactor and father figure.

The performances are hushed and mournful. Foxcatcher showcases a strong and sullen turn by Channing Tatum (Magic Mike, Side Effects) as Mark, and an even-better Mark Ruffalo (Zodiac, The Kids Are All Right) as Dave, who makes up an entire performance out of grace notes – through hesitation, delicacy, twitchiness as he circles the leading duo.

Entombed in makeup and a toucan nose, Steve Carell (Little Miss Sunshine), the same rubber-faced comedian who gave us the dim-witted meteorologist of Anchorman, is the real shock to the system. He delivers a commanding, compellingly creepy portrayal of a man with dead eyes and a cold heart; someone who’s grown up under a withering gaze, who watches over his underlings with the predatory gaze of an eagle, and whose effortful self-containment is second-guessed by a dangerous flicker in his eyes. Stiff, staring, alien, and pathetically funny, he’s a monster of American wealth; a coiled serpent in an ill-fitting tracksuit.

Entombed in makeup and a toucan nose, Steve Carell (Little Miss Sunshine), the same rubber-faced comedian who gave us the dim-witted meteorologist of Anchorman, is the real shock to the system. He delivers a commanding, compellingly creepy portrayal of a man with dead eyes and a cold heart; someone who’s grown up under a withering gaze, who watches over his underlings with the predatory gaze of an eagle, and whose effortful self-containment is second-guessed by a dangerous flicker in his eyes. Stiff, staring, alien, and pathetically funny, he’s a monster of American wealth; a coiled serpent in an ill-fitting tracksuit.

These performances are beyond reproach, which makes it even stranger that the film never quite turns into the crushing experience it should be. Du Pont’s meticulous, airless haven, referred to as the “big house,” may remind you of the mansion from Sunset Blvd. or the motel from Psycho. And as a dark drama masquerading as a sports movie, channelling The Wrestler and The Social Network, it’s most obvious yardstick is Raging Bull – an unfairly impossible measure of a film’s success.

Cannes Best Director winner Bennett Miller (Capote, Moneyball) and his screenwriters thought through every scene, line, and minute of Foxcatcher, which proceeds like a well-constructed argument. The dialogue is spare, rich, and thorny, and essential at understanding the tightly wound triangle at its centre. Miller’s canniest achievement is his depiction of the precariousness of bonds, and how those bonds can shift drastically and imperceptibly. As detailed as a dust-covered oil painting, Foxcatcher is admittedly fascinating in its incremental layering of a bizarre and thoroughly warped character study.

Yet its reasoned and restrained approach – never less than careful and clever – and Greig Fraser’s centuries-old-mausoleum-inspired cinematography, not to mention the punishingly long running time, make for a feeling of funereal sobriety, exacerbated by the oppressive atmosphere of fatalism as it builds to its tragic climax. Foxcatcher reaches for big insights about American ambition and greed and the dangers of unchecked entitlement, while simultaneously treating its real-life subjects like the stars of a Greek tragedy.

As a result, the movie falls prey to the characters’ repression. Few dramas plumb the quirky, unsettling depths of human nature like Foxcatcher, but it proves impossible to embrace because of fundamental miscalculations in craft, set design, and makeup, along with a certain clumsiness in which it overstates its twisted patriotism (watch for the US flags and incessant cheering) and manipulates its sad story into a grand statement on the supposed lack of American values.

In sports, what Foxcatcher does is called “running out the clock.” The performances elevate the material majestically, but can’t bring it across the finish line. It’s basically one long, sick joke played at half speed, maddeningly indistinct, as if the necessary details remain somehow inaccessible to us, when a little less muting might have made it mesmerizing. Instead, Foxcatcher is a good character study with acting so fine that it’s irksome; it’s not in the service of a real, emotional wallop. A win has rarely seemed more self-defeating.

Maps to the Stars (2014) 2.5/4

Virulent, dismal, crackling, and unforgiving, Maps to the Stars is a sickly enjoyable wallow in the scandalous side of show business; a writhing, pharmaceutically heightened waking nightmare; and a grotesque noir vivisectional in its scorn and sadism. It’s a seething cauldron of a film.

A tour through the lives of an LA family chasing celebrity, one another, and the relentless ghosts of their pasts, Maps to the Stars follows the Weiss’s. Agatha (Mia Wasikowska) is a shady schizophrenic who arrives from Florida and lands a job as the personal assistant of Havana Segrand (Julianne Moore), an aging diva with bubblehead mannerisms and a penchant for impromptu threesomes. Stafford (John Cusack) is a self-promoting self-help guru whose “Hour of Personal Power” has brought him A-list clientele. Christina (Olivia Williams) manages the career of their disaffected child-star son, Benjie, a fresh graduate of rehab at age 13.

Cusack exudes telegenic charm when hocking his bestselling guide to holistic healing and dials up the ferocity when dealing with the unwanted Agatha, and Williams (Anna Karenina) matches Cusack ounce for ominous ounce. Cannes Best Actress winner Moore (Don Jon) gets the tricky tone uniquely right, effervescing and spooling disgust, playing Havana like a person walking a tightrope over a yawning pit of psychosis; her rabid emotions threatening her to knock her off and send her plummeting into the abyss. Since The Kids Are All Right, Wasikowska has completed a string of roles doused in intense existential angst (Jane Eyre, Stoker, Only Lovers Left Alive, The Double).

Canadian director David Cronenberg (Videodrome, A History of Violence, Eastern Promises) has nothing left to prove. Working an even deeper haunted groove than David Lynch did in Mulholland Dr., Maps to the Stars is an etched-in-acid comedy that attempts to dig deeper into the perversions and pathologies undergirding the Dream Factory than anything since. While far from his canniest piece of filmmaking, it’s definitely his angriest: Cronenberg constructs his crystal kingdom, then launches his stones with mischievous joy, panning satiric gold from the muck of celebrity ills, in a place where reality depends on your dosage.

Graphic, dark, and horrifying, Cronenberg’s vision is as bright as a sunlamp, as still as a morgue, and as sterile as an operating table, offering no moral stance, full of that dreamy fixation with aberration and perversity. It doesn’t touch Sunset Blvd. or All About Eve, but Cronenberg is on bullish form; the script is dipped in venom – black-hearted to the point of being mean-spirited (there are jokes about being “menopausal” and Mother Teresa being “f***ed up,” and metaphoric singing/dancing on the grave of a young boy) – and the cast is on full power.

Drenched in unhappiness that oozes out of the screen, Maps to the Stars dabbles in every repugnant taboo under the sun – child abandonment, sexual abuse, drug addiction, pyromania, facial disfigurement, hallucinations, animal cruelty, retaliatory menstruation, graveyard wedding ceremonies, incest, murder by strangulation and blunt force trauma, and mass suicide. It’s one of the least sympathetic Hollywood take-downs ever mounted. Cronenberg always does justice to his characters; he just leaves them without hope.

Maps to the Stars is a tale of terminal wastrels with the twisted structure of a Greek tragedy and the rictus grin of a rancorous sitcom. A plaintive chord of melancholy rings throughout, evident in the repeated invocations of Paul Éluard’s poem “Liberty,” a paean to freedom clandestinely published at the height of the Nazi occupation of France. The status-anxiety, fame-vertigo, sexual satiety, and all-encompassing fear of failure which poisons every triumph are displayed with an icy new connoisseurship.

Narratively unwieldy and tonally jumbled, the plot is predictable, melodramatic, and nonsensical, and often comes across as jaded mumbo-jumbo. Yet for a film that has so many problems, it is one of the more watchable ones. It has a venomous bite that makes you think and shudder with outrage. With so many industry neuroses exposed and horrors nested within horrors, one viewing is too much, and not enough.

Scraping away the shiny surface of Hollywood to discover a Cronenbergian outbreak of tortured families, reprehensible behaviour, and extreme violence, Maps to the Stars is an elaborate circus of errors that’s close to the fake smiles and boardroom handshakes of the real thing. It’s a remorseless assault on a Tinseltown stoned on the self-delusion that it’s a hard-working utopia, an altruistic fountain gushing the milk of human kindness, when it’s actually a world comprised of destructive impulses, and designed to breed more of them.