Towards a Less Constitutional Constitutionalism

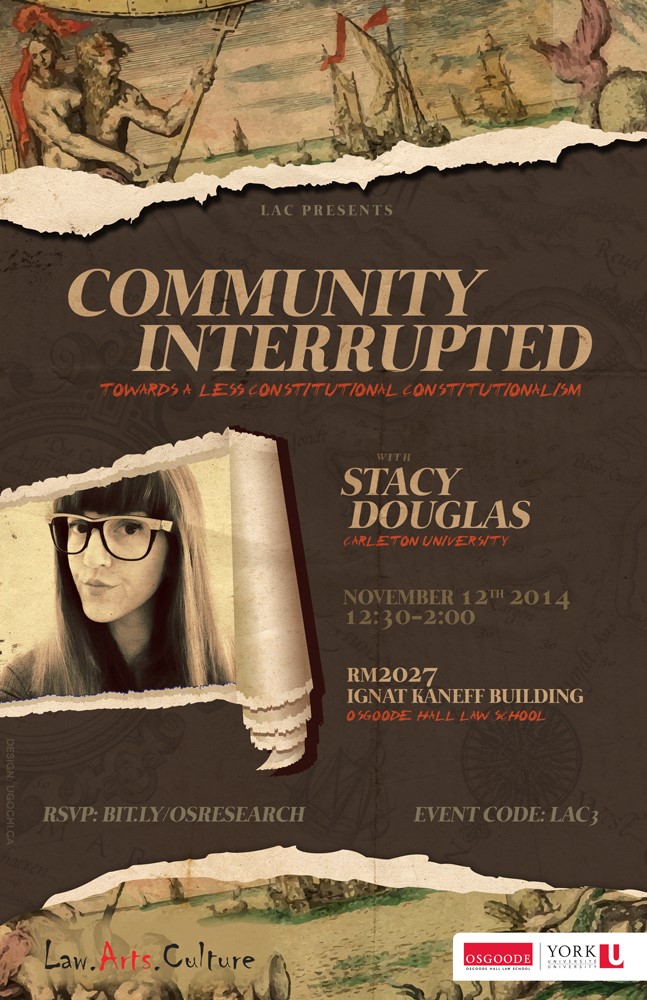

On November 12, 2014, Stacy Douglas, assistant professor at Carleton University and constitutional scholar, visited Osgoode Hall Law School as part of the Law.Art.Culture Colloquium Series. She presented on the problem that constitutions, often considered to be the primary devices with which to construct new political communities, have a tendency to conflate the everyday management of populations with the vast horizons of political possibilities. Her legal interests are motivated by broad questions about theories of democracy, the role of the state, the relationship between government and the governed, and processes of decolonisation.

Currently, she is tackling issues related to monumentalizing the constitution and the need for counter-monumental memorializing in order to interrupt constitutional “fetishizing” and decentre the constitution in the political community. Her research focus is on exploring ways to un-think the hegemony of the liberal subject in the sovereign community, and looking to the museum as a possible place that can function as an external site where radical reflexivity is possible. Prior to her presentation, I had the opportunity to interview Stacy to explore what inspired her research, and the importance of writing the interruption to transform the political community.

Michael: So I read a couple of your articles, your latest ones on constitutionalism and museums. Reflecting on my visits to museums, I never considered them as manufacturers of community, but it’s an interesting thought. What first got you interested in this area of study in the first place?

Stacy: My manuscript begins with an anecdote about me as a young person growing up in Peterborough, Ontario, going on class trips to museums. In particular, I talk about an experience of going to a museum where the staff asked us to assume roles in order to relive history; the role they wanted us to relive was that of settlers coming to Canada. Staff told us, “Pretend you are all immigrants fleeing Europe and you’re getting on the Mayflower and coming to a new land.” I remember distinctly being asked to get into bunk beds that were supposed to help simulate the trip; we all crammed in. They asked us to effectively think and feel the story of who belonged to the supposed history of Peterborough.

That memory has persisted in my mind, begging questions about community and belonging and what kinds of histories are presumed to “belong” to Peterborough. Many of my classmates were not European immigrants, so it wasn’t their story, and it certainly wasn’t the story for my Ojibwa classmates. It’s that narrative force of the museum and its authorizing power that has constantly returned to me.

M: How do you relate how museums function to that of constitutions?

S: That’s a good question. I talk about it in a lot of different ways in my work. The most succinct way I can put it is that both museums and constitutions are sites where imaginations of political communities are launched. They both tell stories about who belongs and who doesn’t belong. They both tell stories about the kind of parameters of community and jurisdiction. And they do that in numerous ways. One example is the use of time—specifically teleological time—the use of linear time to anchor their imaginations of the political.

Crucially, however, even though museums and constitutions have these similarities, I also argue that museums can do things that constitutions cannot and that difference is important. Different kinds of constitutional theorists have tried making the constitution reflexive; what I say there is that the attempt to do so, especially about their boundaries and borders, is not possible. Constitutions delimit; that is what they do. If it’s not delimiting political community or claiming to then it’s not a constitution; it has to have a body politic to found itself.

Museums, even though they have this long history of also delimiting in this way, can actually undo that by adopting counter-monumental memorializing practices. This term, I borrow from South African scholars; they have written a lot about their relatively new constitution (1996), and on the problematic ways it is lauded as a quick fix for their problems. I argue that one of the ways we can attend to this problem is to look at the museum as a site with which we can interrupt that monumentalization.

M: I recently heard Jeffery Hewitt speak on Aboriginal law and evidence, and he was talking about the progression of Aboriginal rights through the Constitution. One thing I took from his talk was that although Aboriginal peoples have rights enshrined in the Constitution Act, 1982, those rights are imposed upon them by, and interpreted through, the sovereign structure in which the Constitution was founded. Museums, on the other hand, are places that don’t have that inherent limitation. Are museums then a source of political community where other people’s narratives, rather than just the dominant one, can be told in a space where we can interact and learn about them?

S: What I am trying to get at are the inheritances of the Western liberal individual that come through our juridical structure. How do we deal with that while simultaneously attending to the everyday need to make decisions, to navigate, and negotiate conflict? While I am aspirational for a juridical structure that gets away from that inheritance of sovereignty, I don’t know how that’s going to happen, I don’t think we can fix it within the system. As long as that system exists, what we should do is to work on not fetishizing it as the sole site of political community. As thinkers dedicated to figuring out how to change our political horizons, we need to stop centering the constitution, or at least realize the limitations of it, and look to other sites from which we can attack these footholds.

M: That’s interesting. A lot of what I’ve heard about Aboriginal law cases, those cases didn’t happen by accident. Aboriginal people violated the law purposefully in order to challenge the law, bring the legal issues to court, and progress their rights through the constitution. It’s also interesting that there may be a second path, outside the Constitution and within the community itself, that can at least advance the cultural narratives on how our communities should look like rather than how they’re imposed on us by the structures of our society.

S: Part of what I’m saying is that it’s not only the constitution that pulls on these inheritances of sovereignty and the Western liberal individual. I think part of the problem is our delimitation of community and our thinking about who is in and who is out. I draw on the work of Jean-Luc Nancy in this regard. Nancy argues that every time we draw a border around community, or any other absolute for that matter, anytime we make this solid, circular boundary and say this is a thing on the inside and it is absolutely autonomous, we are telling a lie about that thing. What happens is that every time we draw that border, it is always exposed to that which is outside of it. It is always in relation. So whenever we say, “Here is the absolutely autonomous individual or nation or community,” whether it is a romanticized indigenous community or a romanticized left multitude or a nation state, any of those things, we’re always telling a lie about that structure, about its autonomy, its sovereignty.

What I am also arguing is that, it is a challenge to un-think that inheritance of sovereignty. What the museum can do (and what a constitution cannot) is interrupt those notions of community found in constitutions and romantic left and right-leaning vanguardist projects. I don’t see this as a descent into postmodern abstraction, but a very political question about how we rethink being together in the world, especially in order to interrogate colonial legacies.

M: In your article on time, constitutionalism, and museums, you mention how the students often got confused or didn’t know what was going on. You wrote that it was an example of how the universalistic structure of the museum fails in its attempt to try to tell a linear version of time. Can you expand on that?

S: Absolutely. I’m glad you brought that up. I had a very good mentor who asked me after my visit to the museum, what surprised me. She encouraged me in my research to think about what stood out, instead of reverting to my expected narratives. What I found were these stories about confusion and frustration. Staff at the British Museum were so intent and focused on their program and project—imparting education on these students—and became very frustrated when students didn’t understand what was going on or didn’t get the meaning of the activity. I used that as an example to show even though the museum attempts to tell a very strong and steady story about itself, it cannot actually hegemonically totalize the world.

It is important to be very careful about projecting our own narratives about these things. I was trying to be attentive to that. In this case, students were supposed to come up with these astrolabes and understand how they work. They didn’t know what was going on; and it was quite funny, but like I said, the staff were quite exasperated.

How I fit that into my own work, into my larger argument, is to say that these kinds of narratives are non-totalizing, unable to suffocate the plurality of the world because there are always things that poke through and interrupt it. However, I argue that it’s not just enough to romanticize those moments. We need to not only think about this, but act. Again, drawing on Nancy, there is an urgent task to actually write the interruption on community and not only rely on these potential moments.

This is where I turn to the possibility of counter-monumental memorializing practices at the museum, using the District Six Museum in Cape Town, South Africa. That museum makes a real concerted effort to interrupt community. I talk about their adult educational programs and the ways they take very seriously the need to interrogate the notions of race, gender, community, the notion of what decolonization and the anti-apartheid city look like because they feel very strongly that the paradigms and the concepts with which they think about those problems today are inherited from colonialism and apartheid. If the racial structure, the very way we understand race, is inherited by the apartheid structure and we’re trying to decolonize, and we’re still using those same concepts—there’s a problem. They take as their political project the interruption and interrogation of all those things. And that, I argue, is the kind of museum practice I want to herald—not the kind of practice that attempts to smooth and cohere and tell a particular liberal or neoliberal story about the community. These counter-monumental memorializing practices can help interrupt those inherited conceptions of community.

M: I guess you can say history is alive then, or museums try to make it alive as an ongoing project, instead of just flattening it over.

S: Yes, I think that’s a good way of putting it. What I like about Nancy’s work is that it echoes a lot of themes found in anti-colonial writing. Critics will rightly say, why cite this European white dude when there are a lot of anti-colonial authors who write about the same stuff? These thinkers are in my work too but I also think Nancy has done some of the deepest rumination on the paradox of community; he goes the full distance in attending to my very particular concerns. For example, however, Nancy’s concept of “being-in-common” resonates strongly with the concept of Ubuntu and the kinds of demands and challenges that the concept of Ubuntu presents us with when we turn to constitutional fetishism.

What Nancy and Mogobe Ramose’s concept of Ubuntu (he is just one theorist on the topic) do is challenge the centrality of the social contract as the delimitation of the political. The social contract as we think of it in contemporary western liberal democracies might help us attend to the utilitarian demands of institutional politics, but if we want to take seriously the questions of inclusion, reconciliation, memory, and justice, then we have to ask much bigger questions.

M: After reading your articles, I was thinking about the Winston Churchill quote “History is written by the victors” and I was thinking about where history is written. Well, history’s enshrined in our Constitution, in the stories told in, for example, the British Museum. So your work goes to interrupting that and destabilizing their functions, so that history gets written by those who have their stories silenced—those that need telling—rather than just the one central normative story that is being told in our society.

S: In a way it is that, and in a way it is more than that, because one of the dangers is the kind of substitution of a romantic conception of history, where history from below becomes the next truth, continuing to rely on these kinds of conceptions. It’s about a constant interrogation of that notion of history and the limits of representation writ large. For example, some of the theorists that talk about counter-monumental memorializing practices talk about this monument called the “Monument Against Fascism” constructed in 1986 in Hamburg. The idea was that they had this massive obelisk and they got all these people from Hamburg to write their names on it, and then, over the next 10 years, they gradually sunk the monument into the ground so that it was gone. For these South African constitutional theorists thinking about counter-monumentalism, they kind of herald this as an example of what they mean. In a way, it is a project that represents that the unrepresentable also exists. We want to have a monument that destroys the very concept of monumentalizing.

The artists claim that the erasure of the monument puts this responsibility on “us” to stand up against justice; in other words, monuments aren’t going to do it for us—we have to do it. Now what I say in my work is that while the monument was an interesting gesture, I question the monumentalizing proclivities of such a statement. The idea imputed here is that we are not “fascists”—but how can we be so sure? We know our concepts of freedom and justice often get tangled in imperialist and colonial projects. The very concept of justice needs to be interrogated. So counter-monumentalizing for me goes even further than the erasure of the monument; it is about writing that interruption and that need to interrupt these narratives. Just getting rid of the monument doesn’t quite do it. You need that constant interrogation of what is being monumentalized – whether in material reality or discursively—and that is why I see that possibility in the museum, the District 6 Museum in particular.

M: So I guess it is important to tackle the big questions, attack the centralized hegemonic institutions that dictate the boundaries of community?

S: In a way, but again, it can also be an interrogation of grassroots organizations that want to romanticize community and say, “We’re the oppressed. We need to have our own story/we need to tell the story.” And there’re larger political questions about that. For example, Amy Lonetree wrote this book called Decolonizing Museums, and she would basically argue against me; she would say that what I am suggesting is a descent into Postmodernism, and when we romanticize this kind of fragmentation and resistance to narrative, especially the narratives of the oppressed, we forget to tell the story of the oppressed. So what she says in the American context is that museums, rather than descending into Postmodernism, need to just tell the story of colonization and how the Indigenous people in the United States have been screwed over because that story isn’t out there. I take that on board.

There is something very important to what she’s saying. On the other hand, I wonder about it as a limited strategy, in terms of bringing in or continuing those inheritances about how we think about community and the individual within it. I’m not sure we can get away from it if we keep perpetuating the same memorializing techniques we’ve been using.

M: I like your idea of destabilizing the constant attempt to memorialize, because for me, even Postmodernism, in its attempt to allow more voices to be heard by removing the tyrannical hegemony, or totalizing center, however you want to put it, creates a void in the middle, a black hole that the fragmentary narratives orbit around. But instead of allowing more voices to be heard, everything gets sucked into it because nothing is allowed to occupy that centre, and nothing is actually being heard. In your view, as the title of your talk “Community Interrupted: To a Less Constitutional Constitutionalism” today suggests, while the centre, the Constitution, stays intact, we have to work to constantly interrupt it, to remind it that it’s delimitation of community is not the be all and end all, not absolute.

S: Absolutely. Rather than romanticize a retreat into “you cannot say anything” or a self-satisfaction in fragmentation, we need to have that constant engagement, that writing of the interruption. What I am arguing is not a rejection of constitutionalism, but a defetishization of it: the lessening of the centrality of the Constitution, while simultaneously writing the interruption. Those two things together are what I am articulating as a counter-monumental constitutionalism.