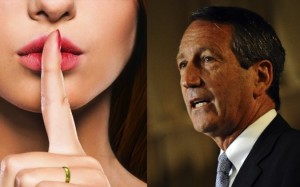

Have an affair. Compromise your privacy. Face professional misconduct charges.

lives. Millions of people have affairs —politicians and lawyers are no exception. Photo credit: Thewire.com

To the incoming class of 2018, let the Obiter Dicta be one of many to welcome you to Osgoode! Today you take the first step on a journey of a thousand miles. Your introduction to the practice of law begins with what is referred to simultaneously as the most and least relevant class of the JD program: Ethical Lawyering in the Global Community. Before reveling in the wit of Lord Denning, you must first become acquainted with all seven chapters of the LSUC’s Rules of Professional Conduct. In addition, your conceptions of morality and ethics will be challenged through episodes of The Practice and lively mock trials. You may be confronted with dilemmas that involve sweatshops in Indonesia, disposing of key evidence, and looming brain aneurisms. To help prepare you for what awaits, I ask the following question: To what extent should a lawyer’s private morals inform their professional ethics?

This question has become especially relevant in the legal community with the recent Ashley Madison data leaks. For those unaware, Ashley Madison is an online dating service for married individuals looking to have an affair. The hacker group Impact Team released over 9.7 gigabytes of account details for nearly 32 million users of the site on August 18. Several of these user profiles have been linked to Bay Street firms, sparking debate over whether adultery should be subject to discipline under the LSUC’s Rules on professional integrity. The supporting argument is premised on the idea that these acts negatively impact the lawyer’s credibility. It is suggested that a lawyer who actively pursues an opportunity to break their wedding vows can be equated to someone without fidelity to their word, and therefore untrustworthy as both a spouse and a lawyer.

The issue forces an examination of the nexus between a lawyer’s private life and its impact on their professional obligations. Author Daniel R. Coquillette writes that the law is “not merely a trade but rather a profession, which entails a higher calling in pursuit of the public interest.” He suggests that it is a delusion of young, inexperienced lawyers to think they can separate their personal lives from their professional ones, or that they can separate their personal and professional ethics. The philosophical underpinnings of this line can be found in Plato’s Republic, where it is argued that the members of the guardian class have no private life apart from their political duties. It could be said that by virtue of taking on the responsibility of certain occupations such as a politician and lawyer, the private individual makes himself publicly available. This may be seen as implicit consent to be publicly scrutinized for both public and private action.

Many hold the belief that lawyers should be held to a higher standard in order to justify their privileged position in society. The Federation of Law Societies of Canada has addressed the question of whether lawyers are bound by their code of professional conduct in all respects and at all times. It was the Federation’s position that lawyers are bound at all times by their code of professional conduct when their conduct relates to the protection of the public, respect for the rule of law, or the administration of justice. The Federation also confirmed that a special ethical and social responsibility comes with membership in the legal profession, and the unique and privileged position that a lawyer holds in society requires the lawyer to refrain from acts that are derogatory to the dignity of the profession.

The commentary for the LSUC’s Rules on integrity speaks to how a lawyer’s dishonourable or questionable conduct in either their private life or professional practice can reflect adversely on the integrity of the profession and the administration of justice. However, it also notes that the Law Society will not concern itself with the purely private or extra-professional activities of a lawyer that do not bring the lawyer’s professional integrity into. This does little to clarify whether adultery can be viewed as a purely private activity that does not bring professional integrity into question. For additional guidance, the CBA Code of Professional Conduct provides illustrations of conduct that may be viewed as dishonourable or questionable. The most relevant example cited is committing any personally disgraceful or morally reprehensible offence that reflects upon the lawyer’s integrity (of which a conviction by a competent court would be prima facie evidence). This language seems to suggest that the offensive behaviour ought to be illegal to attract the attention of the Law Society. Though distasteful and grounds for divorce, adultery is not necessarily a criminal offence.

Finally, in looking at the ABA’s Model Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 8.4 deals with professional misconduct. In its commentary, the ABA describes the concept of “moral turpitude.” This is construed to include offences concerning matters of personal morality, such as adultery, that have no specific connection to fitness for the practice of law. The commentary further states that a lawyer should be professionally answerable only for offences that indicate a lack of those characteristics relevant to law practice such as those involving violence, dishonesty, breach of trust, or serious interference with the administration of justice. From this description, can infidelity to a spouse be evidence of dishonesty and breach of trust to the extent that in such a narrow context these are relevant to the practice of law? To be sure, a lawyer who breaks their marriage vows has committed a breach of trust to their spouse. However, can it fairly be said that this dishonesty should be a reflection of their capability to perform their ethical duties as a lawyer? It raises the question of whether a bad person can be a good professional. Further, would we hold a professional engineer or a physician against this same heightened level of scrutiny?

Assuming that private life falls within the scope of professional scrutiny, the next challenge is defining what we consider good moral behaviour. With a rapidly changing social and moral context from which to develop such standards, it seems impossible to come to a general consensus about what bar (my apologies for the distasteful pun) to measure these professionals against. It is clear that we do not have a shared community standard about sexual activities. Bill Clinton’s situation during his U.S. presidency demonstrated that much of the public was able to compartmentalize the president’s professional obligations from his private life. The public understood that it is perfectly possible to be competent in one area while, arguably, dysfunctional in another. Clinton is also not an isolated incident. There are countless stories of politicians, media personalities, and others in the public eye who have indulged in equally salacious indiscretions. While for some, this signaled the end of their career—Anthony Weiner and Jian Ghomeshi—for others it certainly did not—Pierre Trudeau and Donald Trump.

It’s interesting to note that broad definitions of personal misconduct arguably can be used to exclude certain classes of “undesirables” from the profession. Requiring individuals to have an unsullied private life in addition to their professional excellence may significantly reduce the number of eligible applicants to the bar, leaving only those of a certain social class carrying a very particular set of values. In a somewhat ironic twist, rigorous adherence to a set of standards that very few can meet creates a misperception of the profession as elitist, which seems at odds with the very concept of professionalism. If nothing else though, this could amount to an innovate solution to address the current articling crisis across the country. Welcome to the first day of the rest of your lives, Class of 2018!