The importance of a memorable judicial writing style

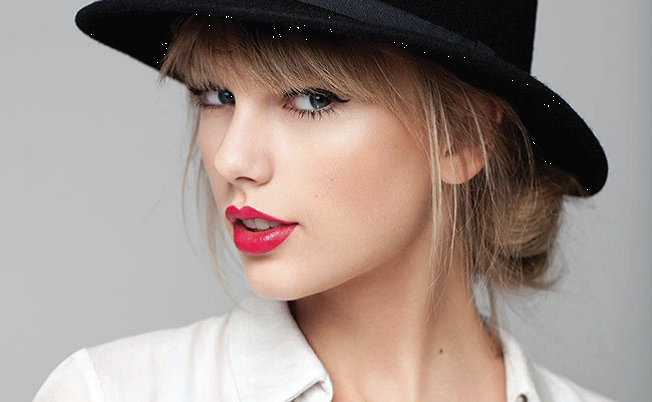

Judge Gail Standish, a former intellectual property lawyer and current district judge in California, made headlines last week with her dismissal of a copyright claim against Taylor Swift’s “Shake it Off.” Swift was being sued for $42 million in damages by musician Jesse Braham, who claimed that the repetition of “players gonna play,” “haters gonna hate,” and “fakers gonna fake,” came directly from a song that he wrote in 2013 (entitled “Haters Gone Hate,” of course). In her dismissal, Judge Standish quoted not one, but four different Taylor Swift songs, incorporating the lyrics into the reasons for her judgement, with hilarious lines such as “…for now we’ve got problems, and the Court is not sure Braham can solve them.” She also made reference to Urban Dictionary and a 3LW song from 2000 named “Players Gon’ Play.”

What I found fascinating about this case was not the seemingly frivolous lawsuit, but the amount of press the dismissal received. Judge Standish’s use of common language and (gasp!) puns, caused non-lawyers to read a judicial decision. Numerous people who generally couldn’t care less about legal issues were all of a sudden tweeting, posting, and tagging her dismissal.

Traditionalists may say that judicial decisions are no place for commonalities and Taylor Swift quotes, but I respectfully disagree. Making court decisions more accessible to the average person is something to be praised, and judges should be encouraged to spare the legalese and instead tell a story. The United States has attempted to start the movement away from bureaucratic jargon with the Plain Writing Act,signed by President Obama in 2010, which requires federal agencies to use language that “the public can understand and use.”

A memorable and clearly written decision is not only important to students and practitioners of the law—who need to be able to use the law effectively—but also to other players in the judicial system, namely, the plaintiffs and defendants that have every right to read and understand the verdicts in their cases. To illustrate the impact of a strong narrative in judicial writing, I thought I’d go over a decision of everyone’s favourite “judge of the people,” as well as a more recent case from earlier this year that was so powerful I will never forget it.

I’m pretty sure Lord Denning occupies a special place in almost every law student’s heart, and his decisions—love them for their down to earth language (and utter disregard for the common law) or hate them for their obsession with cricket (and utter disregard for the common law)— are, at the very least, among the most memorable that anyone reads in 1L. Personally, I was pretty pissed off at him by the time I was writing my first law school exams, but his personal style has been influential in judicial decisions ever since he first sat on the bench. One of his lasting legacies is his use of actual names, as opposed to the titles “plaintiff” or “appellant.”

Miller v Jackson, one of the all-time great Lord Denning decisions, starts out with “In the summertime village cricket is the delight of everyone.” In case you haven’t read it, a homeowner was seeking an injunction on a cricket ground, due to the fact that cricket balls were being launched into the property during practices and matches. I remember exactly where I was sitting in the library when I read it for the first time, sighing very loudly numerous times. It was that time of year where I was so stressed and burdened with schoolwork that the idea of a judge using his love of cricket to inform his decision made me furious. I had enough to deal with! But looking back, I absolutely love the case, and most of all, Lord Denning’s use of language to tell a story. Not only because creative writing such as this helps one to remember the facts, but also because, in all honesty, I would probably write a similar decision if the sport in question was baseball. Lord Denning took what was a relatively straightforward torts case on negligence and nuisance and really made it into something special. Most memorable line: “The animals did not mind the cricket.”

Plain language in a judicial decision can also be used to show empathy and compassion towards offenders. On 11 February 2015, Justice Nakatsuru of the Ontario Court of Justice wrote his decision in a case called R v Armitage. Regarding precedent, in what might not be the most important or prestigious case, I hope it does become an influential one, due to the judge’s use of poetic language and consideration towards those reading his decision. Jesse Armitage is an aboriginal man who was a repeat offender, often getting into a pattern of stealing money and goods from stores and restaurants. His grandmother was an Indian Residential School survivor, and he ran away from home at 15. His troubled life clearly spoke to Justice Nakatsuru, and in response, Justice Nakatsuru spoke to him, directly, in his decision. He starts out early by saying, “In this case, I am writing for Jesse Armitage,” and later goes on to describe him as “a tree, whose roots remain hidden in the ground.” I can’t do it justice—if you have a moment, and are interested in criminal law, aboriginal law, or even just plain good writing, I suggest you read it. It’s not long. But don’t blame me if something gets in your eye afterwards.