Do we always know when we’re being marketed to?

Every day on our way to school, work, or home, when we are watching TV, listening to the radio, or are surfing social media, we may be exposed to pharmaceutical industry marketing campaigns, whether we know it or not. Is there anything wrong with being exposed to industry marketing? Well, it depends.

In order to answer this question, we must ask some tough questions. Do we know that we are being marketed to by viewing or listening to certain content? If yes, do we take the information with a grain of salt or glance past it like we might when we see just another car commercial? If we don’t know that content is intended for marketing, are we less likely to mute the television, change the radio station, or flip past the article? If content is focused on a disease state or disease category without mentioning a drug, is it still marketing?

The answer is yes, and the public relations (PR) companies that pharmaceutical companies hire for their marketing know this. So, these companies have developed marketing strategies to mask the involvement of industry in what looks like medical education for both physicians and the public. From medical ghostwriting and ghost marketing in peer-reviewed academic medical journals of varying impact factors, to continuing medical education for doctors, unbranded articles in the mainstream media, drug companies’ marketing campaigns are shaping the ways we think about medical conditions requiring drug treatments and our doctors’ prescribing choices.

Over the past decade, in the United States, Big Pharma has paid over US$30 billion in civil settlements and criminal penalties to federal and state departments for illegal marketing practices, overcharging Medicaid, and paying kickbacks. Illegal marketing practices have received more attention in the US than in Canada, likely partly because of the presence of whistleblower laws. In fact, as a result of lawsuits in the US against drug companies, thousands of internal industry marketing documents are now housed in an online archive called the Drug Industry Document Archive (DIDA). This archive is publicly accessible and allows us to dive into some of the strategies that drug companies use to illegally market their drugs. (The archive also contains over fourteen million documents about the tobacco industry’s internal practices, but we can save this discussion for another time).

Why does knowledge of these fines and illegal pharmaceutical company marketing activity in the US matter to those of us across the border? Simply because we receive much of the same content that Americans receive. The Canadian population and doctors rely on American medical journals for some important medical information on clinical trials, secondary data analyses, and other treatment information. What’s the problem? This marketing does not look like marketing at all. It looks like educational articles, awareness campaigns, or lifestyle articles.

The CBC reports a recent example of one such lifestyle article published in a Canadian newspaper, the Globe and Mail, that was developed as part of an “unbranded campaign” by a Canadian drug company, involving a popular Canadian comedian, a doctor, and a PR firm. The article, published by the Globe and Mail, appears as a regular news article, but was arranged by a PR company. This marketing comedian appears to have authored an article with the aim of “get[ting] women to start talking about female sexual health after menopause” (source, CBC). But it wasn’t the comedian who stated this—it was the PR company, which contacted the CBC to pitch an interview with the comedian to appear as a “lighthearted lifestyle piece,” without mention of the involvement of the drug company.

When the CBC inquired about whether a drug company was involved, the PR company responded yes. This company manufactures a prescription medication that treats a condition related to the created disease state on which the interview was to focus. In the PR company’s response to the CBC, it also stated that “No parties, including [the PR company] want any mention of the drug or drug company…It is an unbranded campaign” (source, CBC), meaning that the drug that the company is marketing is never mentioned in the campaign. Rather, the condition is marketed and women are told to “talk to their doctors.” These types of campaigns create a buzz about a condition that naturally occurs and turns the condition into a pathological diagnosis, that could otherwise be treated without medication. In response to the CBC’s inquiry, the drug company stated that “In Canada, pharmaceutical companies are permitted to provide factual, fair, balanced, and non-promotional information to the public on health and diseases” (source, CBC). Under these rules by Health Canada, this type of article would be considered a “help seeking announcement” and companies are allowed to mention neither their names, nor the name of a drug. Although superficially it seems that this article doesn’t breach these rules, we must consider the intent of the rules and the reasons for and context in which this information is provided. We must also consider whether the method of the provision of information was truly balanced, what information was prioritized, and what information was minimized. We also must consider the role of a PR company when hired by a drug company and why a PR company would be hired to facilitate an “unbranded campaign.”

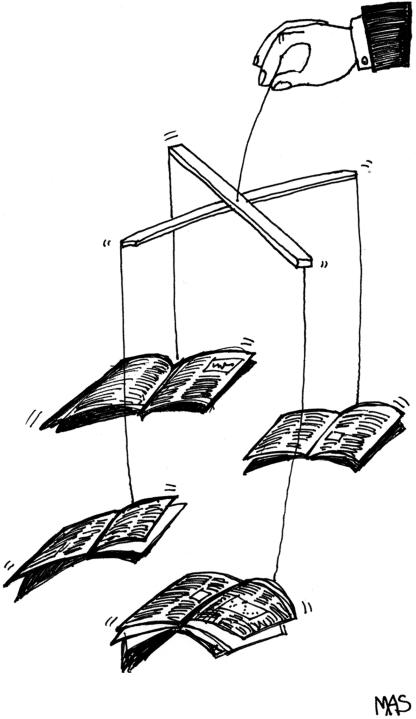

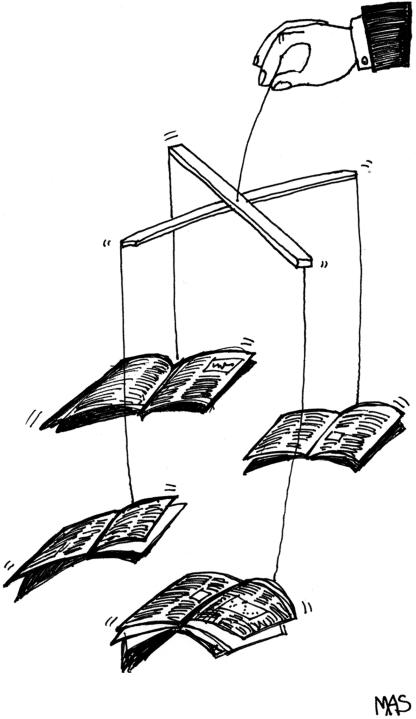

These sorts of campaigns can be part of a larger marketing strategy called ghost management, in which a drug and PR company control not only the data that is released on a drug or condition, but also the shaping of the interpretation of that data and who receives it. These campaigns can begin years before a company’s drug is on the market, so it wouldn’t be surprising if we hear more about post-menopausal conditions in the coming years in preparation for the approval of these new “lifestyle drugs.”

The academic literature on drug company marketing practices suggests that much of the scientific literature base that we believe to be objective, academic science, is actually ghost managed and ghostwritten, with prominent doctors signing their names to the articles to provide the published data with credibility. There is also evidence in the DIDA of such ghostwritten articles being published in the highest-impact academic medical journals and the back-and-forth email exchanges between the medical writers (ghostwriters) and the “guest authors.” Understanding the various components and how they work together to, over time, create a marketing strategy that sells, means understanding the significance of what may at first seem like potentially trivial interviews, news stories, or articles.

This article was written by Adrienne Shnier, who received her PhD from the School of Health Policy and Management at York University and specialized in medical education and pharmaceutical industry promotion.

This article is part of the Osgoode Health Law Association’s Perspectives in Health column. Keep up to date with the HLA on Facebook (Osgoode Health Law Association, Osgoode Health Law Association Forum) and Twitter (@OzHealthLaw).