On September 25 residents living in KRG-controlled areas will vote on whether Iraqi Kurdistan should sever itself from Baghdad and become an independent state. For now, we can assume that at least Israel will support the Kurds seizing the reins over their own destiny. This unique amity is the fruit of a mutual apprehension of an imploding Arab world and the security threats posed by Turkey and, of course, Iran.

The rest of the world, however, seems quite opposed to it. Just about every relevant state—Britain, Russia, Germany, and the United States—has unequivocally withheld its support. Baghdad, Tehran, and Ankara lead the fiercest opposition to Kurdish independence, as it would inevitably spur the Kurds in neighboring countries to expect a similar national emancipation. Unfortunately, the Kurds are at the center of the twenty-first century’s Great Game: new players, new stakes—same rules.

A Brief History of the Kurds

Regional and global powers have historically subordinated the Kurdish struggle for independence to their own geostrategic interests. Following the Great War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the British sought to use the Kurds as a bulwark to the territorial ambitions of a recalcitrant Turkish general, Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk), who rejected the Allied partitioning of Anatolia. Kurdistan, however, lacked a consolidated nationalism and was instead driven by intra-Kurdish divisions, blood rivalries, and tribal enmities that not even the prospect of independence could put asunder. As the British High Commissioner recognized at the time: “there [was] no such thing as Kurdish opinion.”

Nevertheless, in 1920 the Treaty of Sevres conceded to the Kurds autonomy pending the approval of a League of Nations commission. But Istanbul’s surrenderism was less the consequence of a free and informed decision than a capitulation to the Allied forces that surrounded the city. The Kemalists, acting independently of the de jure regime, waged an all-out, existential war on Turkey’s interlopers.

They succeeded in crushing the Kurds, in extricating the Armenians, the Italians and the Greeks, and in disabusing France and Great Britain of any imperial designs. Under these less auspicious circumstances, another treaty was clinched at Lausanne in 1923. It was denuded of Sevres’ promises and clad with Allied concessions. Thus the integrity of Anatolia was maintained, and by 1926 the Mosul vilayet, a territory in northern Iraq inhabited largely by Kurds, was conclusively brought under Baghdad’s heel.

And so began nearly a century of resistance.

Over the 1930s and 1940s there were intermittent uprisings in Iraq, some amounting to skirmishes and others full-scale revolts. They were mainly driven by economic or tribal grievances but occasionally shrouded in nationalist pretensions. One enduring complaint regarded Baghdad’s refusal to protect the linguistic and cultural rights promised to the Kurds by the League of Nations in 1926.

The Kurdish Democratic Party’s (KDP) first breakthrough came after the overthrow of the ancien regime in 1958. The new republic’s leader, President Abd al-Karim Qasim, invited an exiled Mullah Mustafa Barzani back to Iraq and released a provisional constitution that considered Kurds “partners” to the Arabs with “national rights.” Iraq was now a bi-national state. Recognition, however, did not translate into any tangible legal or political changes.

In 1970 then-Vice President Saddam Hussein entered Kurdistan to resolve a conflict for which there were only tens of thousands of casualties to account. On 11 March Barzani and Saddam reached the best deal the Kurds had hitherto received. Inter alia, it protected the linguistic, cultural, and economic rights of the Kurds and also provided for the unification of areas with a Kurdish majority as a self-governing unit.

But this rapprochement faded rapidly. In 1972 Baghdad nationalized its oil sector and signed a 15-year treaty of friendship with the USSR, bringing Iraq firmly into the Cold War’s fold. By 1974 Barzani was receiving aid from the U.S., Iran, and Israel to bolster his peshmerga’s military prowess. Under the misapprehension that the U.S. had a genuine interest in seeing a Kurdish national movement succeed, Barzani spurned Saddam’s overture for a peaceful reconciliation. This decision would be one of his last.

In 1975 Iran and Iraq met in Algiers at an OPEC conference and resolved a territorial dispute on the Shatt al-Arab waterway. The deal required that Tehran cease its operations in northern Iraq and withdraw its surface-to-air missiles from the border, as it did immediately following the accord. Predictably, Barzani’s forces collapsed and the resistance with it. He died from cancer four years later.

The era of diplomacy had now expired. In the latter half of the Iraq-Iran war (1980-1988), the Kurds worked alongside Tehran, allowing its forces to freely penetrate the northern border. President Hussein enlisted his cousin General Ali Hassan al-Majid to move against and comprehensively defeat the Kurds. Looking to repeat history, he answered the “Kurdish Question” with an Iraqi rendition of the Final Solution.

Chemical Ali, as he later came to be known, launched the Al Anfal campaign in 1987. Before moving his troops into the villages or cities, he first saturated the air with sarin gas to weaken defenses and terrorize civilians. Thousands of villages were razed and millions were made refugees. Yet the international response was mute. The C.I.A. was busy sharing intelligence with Iraq while various European countries were selling Saddam’s regime sensitive materials, thereby implicating themselves in a hideous, but widely ignored, genocide.

It was not until after the Iraq-Iran ceasefire in August that the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) passed Resolution 620 condemning the attacks. But by that point it was too late, for between 150,000 and 200,000 Kurds had already perished, and, in any event, Baghdad continued to use chemical weapons until October.

This juncture sharply contrasts with the concerted response of the international community after Iraq annexed Kuwait in 1990. Despite the regime’s authoritarianism, it supplied the world with a fabulous amount of oil, something Kurdistan could never quite get its hands on. After the Coalition’s swift defeat of Iraqi forces in February 1991, the Shi’a and Kurds rose up to topple the regime.

This so-called “Revolution” had the trappings of a standard Kurdish uprising: encouragement followed by betrayal. The world stood idly by as the Iraqi government turned its streets into open-air abattoirs. The U.S. certainly wanted a replacement of Saddam, but not a replacement of the government, as it feared that an implosion would unleash the ethnic and religious tensions that the Ba’athists violently kept neutralised. Thus Baghdad regrouped, crushed the Shia rebellion in the south and marched its Republican Guard northward. Only three years after Al Anfal another 20,000 or so Kurds had been mercilessly slaughtered, with little more than a blip coming from the international community.

It was not until the “CNN Effect” materialised that the Kurds got their reprieve. Well over a million refugees poured over the Turkish and Iranian borders, and heart-rending images of men, women, and children wounded, starving, and tenuously gripping onto life found their way into the homes of the general public. A furore erupted. Under domestic and international pressure, the U.S. launched operation Provide Comfort, creating a no-fly zone over parts of northern and southern Iraq for returning refugees.

Another small victory for the Kurds came on 5 April 1991 when UNSCR 688 was passed, condemning the repression of Iraqi citizens, especially Kurds. This was significant as it was the first time the Kurds had been recognized in an international document since the League of Nation’s had done so in 1926.

Kurdistan After the Revolution

By October Saddam had slapped asphyxiating sanctions on the nascent autonomous region of Kurdistan. The KDP and PUK (Patriotic Union of Kurdistan) reconciled their differences and set up a democratic administration in 1992 to govern the area. In the end, a nearly equal distribution of votes correlated to a 50/50 split of important posts between the two major parties. The Kurdistan Regional Government failed to garner recognition from abroad, but nevertheless was invested with significant powers. The KRG now had control over their cultural and linguistic rights, something for which hundreds of thousands of Kurds over several generations had fought and died. And although battered and moribund, they now had greater control over their economy.

Seventy years of resistance was finally beginning to pay off.

Standing on the mountains and peering over Sulaymaniyah, one can visibly see the progress that Kurdistan has made since its first democratic election. Invariably, Kurdish locals wave their arms and pace back-and-forth dangerously close to the precipice to draw out for you the city’s expansion following the Anglo-American invasion in 2003. Indeed, only two years later Iraq had its first (January) and second (December) free and fair election—the ‘free and fair’ bit being the most important feature.

The new Iraqi National Assembly was tasked with devising a constitution amenable to the interests of religious groups—Christians, Sunnis and Shi’ites—as well as ethnic groups—Turkomans, Arabs, Kurds—in addition to several other minorities. The motley concoction of Iraq’s inhabitants did not make this task simple. Nevertheless, the Kurds, for their part, succeeded in entrenching their gains and turning their de facto autonomy into law.

The KRG was given fixed borders and now had the legal right to retain its own militia force. It was granted exclusive control over the region’s land and water rights. But in recent years, constitutional provisions that had been intentionally left vague in 2005 have helped rally Baghdad and Arbil against each other. And there are no assurances that these disputes will be settled off the battlefield.

Why Kurdistan Is Not Ready for Independence

On account of the foregoing, it is clear that the moral argument overwhelmingly favours Arbil parting ways with Baghdad. The whole genocide bit was probably enough, but the decades of oppression and needless misery certainly gives the argument its coup de grace.

If only the question was so simple.

According to the political, military and economic argument—and just about every other indicium one can conjure up—independence will almost certainly augur a future of destitution, isolation, and, worst of all, subordination.

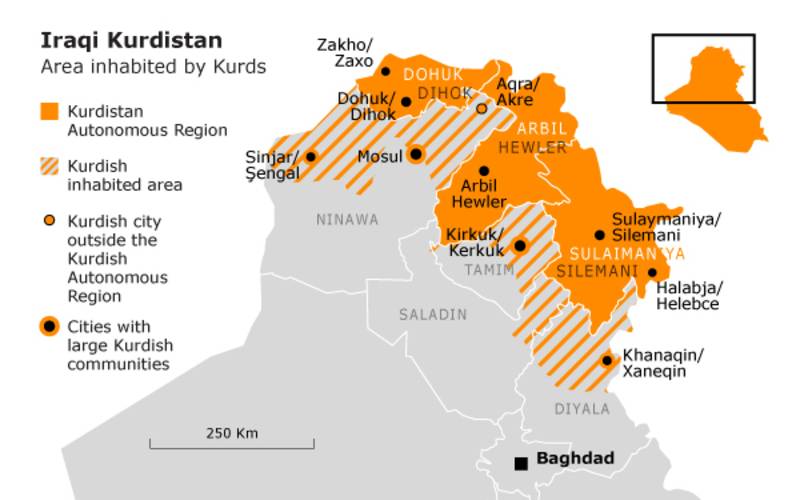

The most contentious feature of the referendum concerns the status of the “disputed territories,” particularly Kirkuk and Shingal. These are territories that Baghdad asserts are part of Iraq proper, but which the KRG holds as essential to the Kurdistan region. The legal means to resolve these disputes is found in Article 140 of the Iraqi constitution, which recommends a step toward normalization followed by a census, and that a referendum be held to determine the will of the people. This procedure, however, was supposed to be completed no later than 31 December 2007.

There are two “camps” competing for the Shingal district. On one side is the Turkey-KDP axis and on the other is the PKK-Iraq-PUK-Iran alignment, which enjoys less of an ideological alliance than a tenuous shared-interest of transitory convenience.

Shingal’s prize feature is not only that it sits on the former IS supply route from Mosul to Raqqa, but also that there may be large, untapped oil reserves in the area. And as of right now the KRG and Turkey have closed their borders to northern Syria, where PKK-linked YPG/PYD Kurdish forces are governing. Having control over Shingal, then, would provide the KRG with additional leverage over its neighbours, and Rojava (west Kurdistan) with an economic lifeline to Baghdad and the rest of the world.

But this is all a non-starter for Turkey. There are no circumstances under which it will permit PKK-linked forces—in the form of the Shingal Protection Units (YBS)—to retain control over the area. It fears the district and its mountains will provide the PKK with a second Qandil, a region in northeastern Iraq where the militant group has been recruiting and training new cadres since the 1990s. At the very least, PKK control over the Shingal district may develop into a shock absorber in the event of a Turkish attack in Syria, or a place of refuge for fighters bombed out of Qandil.

Nor will Turkey allow Tehran-loyal Hashd al-Sha’abi militias to consolidate their control over Shingal. This would project Iranian power uneasily close to Turkey’s border, and would help secure a “Shia Crescent” from Iran to Lebanon, a prospect that is also liable to antagonize the U.S. and Israel. Iran also has an interest in keeping PKK out of Qandil, since that inevitably invites Turkish forces close to its own border.

But Turkey has already showcased its intentions to thwart any outcome where its own proxies do not prevail. Since 2015 it has been strengthening its forces in the Iraqi city of Bashiqa with a KDP endorsement, and President Erdogan has ordered attacks against PKK-linked groups in Shingal as late as 25 April.

Mahma Khalil, the mayor of Shingal, told Basnews that Yazidis wanted to be part of an independent Kurdistan. But his announcement is the product of a KDP patronage network that purchases the affinity of Shingal’s elites, but not its people. If it comes down to a referendum, the Yazidis—many if not most of whom remain IDPs and refugees—would probably elect to remain in an Iraqi federation. Ideally the Yazidis would like to have greater control over their own governance, something which the KDP is unlikely to brook. And as a result of callous mistreatment over the years, residents of Shingal feel a deep-seated disdain and suspicion of the peshmerga.

In August 2014, when IS was approaching the area after seizing Mosul in June, the peshmerga abandoned the Yazidis, leaving them without sufficient arms or defences. The massacre that followed turned genocidal. Thousands of men, women, and children were stacked in mass graves while girls were sold into sex slavery. It was only in November the following year that the region was recaptured. The PKK was the only local force initially willing to come to their rescue and the Yazidis are not likely to forget this.

Then there is the problem of Kirkuk. It sits on one of Iraq’s largest oil reserves and offers the surest and fastest path to economic independence. The city is broken up into thirds. Less than a third are Arab and Assyrian, one third are Kurdish, and just over one third are Turkoman. The PUK and KDP have secured the city and continue to defend it against IS onslaughts launched from Hawija.

But the Turkoman are apprehensive about the Kurds, share an ethnic affinity for Turkey, and are likely to vote to stay inside Iraq’s orbit.

By all means, then, the Kurds are not likely to prevail from a free and fair referendum. Given the indispensability of these regions, it is very possible that the KRG will resort to force to secure their interests. In fact, one can count on it.

The current state of the KRG’s economic situation is also worrisome. After the 2014 “oil-for-revenue” deal broke down between Arbil and Baghdad, the KRG started to sell oil on its own accord. But this has largely been a diplomatic and economic blunder. The Iraqi Kurds now depend heavily on Turkey to sustain its economy, and tensions with Baghdad have encouraged an exodus of international oil companies. Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi has also ceased paying the KRG 17 percent of the federal budget, a painful hit to an economy already in tatters.

Moreover, selling oil without Baghdad’s consent has had legal ramifications. On July 4, for example, Reuters reported that Canada ordered the seizure of a 720 000-barrel cargo of crude from Kirkuk as requested by the Iraqi Oil Ministry. Baghdad has further threatened to take its complaints to international legal bodies against those countries, particularly Turkey, which purchase oil directly from the Kurds. Despite perhaps being the most effective force against the Islamic State, the Kurds evidently still do not enjoy the diplomatic cover to prevent their independence from turning into isolation.

The Iraqi economy has been doubly battered by the influx of refugees and internally displaced persons fleeing IS-controlled areas. Unemployment is high and the KRG has had difficulty paying its workers. Painful austerity measures have shrunk the budget by over $10 billion USD since 2014 when global oil prices first plummeted. Half-finished construction projects and derelict infrastructure can be spotted all over major cities. It is arguable that independence will only worsen the crisis.

With Syria in shambles, Baghdad irate, and Iran naturally chary to support Kurdish autonomy, President Barzani has built a house of cards with Ankara as its foundation. Now the KRG’s sole egress to the outside world is tethered to the whims of a government which has historically attempted genocide against its own Kurdish population and which also continues to fight a brutal, decades-long war with the PKK. Slim pickings, I suppose.

And the bad news does not end there. The KRG is about as internally divided as it is externally isolated. In 2005 Barzani was appointed president and in 2009 he was re-elected. In 2013 his incumbency was extended till 2015 through a combination of legislative sleights and political ruse. But none of this matters since it is 2017 and he still has not abdicated.

Instead, he has arrogated dictatorial authority over parliament. After protests against Barzani’s leadership erupted in Sulaymaniyah in 2015, he blamed the Gorran party for the violence that ensued and barred its members from entering Arbil. Since Gorran has 25 seats (the second most) and holds the position of Speaker, parliament had been—and has since been—suspended indefinitely. It just so happens that the premiership is held by his nephew, Nechirvan Barzani, who alongside his uncle now rules over the tribal democracy that the KRG has become, which more often than not falls closer to the adjective than the noun.

Worst of all, the two major parties have divided Iraqi Kurdistan into modern fiefdoms. Between 1996 and 2006 Iraqi Kurdistan was separated into a “green zone” and a “yellow zone,” the former being the region over which the PUK exerted control and the latter referring to the KDP’s ambit. A similar de facto arrangement endures today between Arbil and Sulaymaniyah. With the suspension of parliament and with a brute running the presidency, both parties have returned to this collision course with potentially ruinous consequences.

To restart a project that commenced 12 years earlier, in 2006 the KDP and PUK reached an agreement to unify their respective forces and depoliticize the peshmerga. About 40,000 fighters are now nominally under the Ministry of Peshmerga’s control, which is nominally headed by a Gorran member of parliament. But that still leaves well over 100,000 directly beholden to political parties.

Some peshmerga allegiances even break down to an individual level. Bafel Talabani of the PUK, for example, commands an anti-terror force that is not under the authority of any ministry, while Nechirwan Barzani has a personal security force that helped protect Kirkuk oil fields in 2014. This phenomenon is widespread. Thus Kurdistan is composed not of a monopoly but an oligopoly of force, whereby pockets of power dominate across political, ideological, and tribal lines.

Historically these divisions have allowed for outside powers to sow chaos inside the region, pitting the Talabani crew against Barzani’s and vice versa. In the midst of the civil war between 1994-1998, Barzani enlisted Saddam Hussein to oust the PUK from Arbil and crush the KDP’s opposition, while the PUK sought Iran’s backing to defend itself and retake the offensive. The war did not end till Washington brokered an agreement and after 1000 Kurds already lay dead.

More recently, rivalries between the parties has weakened Kurdish resolve against the Islamic State. For example, Muhammed Haji Mahmud, the secretary-general of the Kurdistan Socialist Democratic Party, who was charged with defending Kirkuk in 2014, has lamented the difficulty he had in mounting a concerted attack against IS when his subordinates were bound to political parties rather than being bound to Kurdistan generally. Furthermore, when IS launched its attack on Shingal in 2014, the KDP was accused of focusing more on territorial contestation with the PUK in Kirkuk than in defending the area from a horde of radical Islamic murderers bent on exterminating Yazidis.

Conclusion

There are compelling reasons to be captivated by the marvel that Kurds are. Despite living in what is arguably the world’s most unhospitable region, surrounded by Iran, Baghdad, Syria, and Turkey, the people have emerged out the ashes as freedom-loving humans that yearn for peace, equality, and recognition. The people understand the importance of free speech, the freedom of religion, and the emancipation of women (with some qualifications on that last bit). The people have an affinity for “the West”  and all its virtues (and, indeed, some of its vices). It is the government which has betrayed their struggle and it is the region’s religious fascists and pseudo-secularists who insist on repressing them.

and all its virtues (and, indeed, some of its vices). It is the government which has betrayed their struggle and it is the region’s religious fascists and pseudo-secularists who insist on repressing them.

Thus while the people are ready for independence, the KRG and the world are not. On September 25, Kurds must go out and vote “yes” for severing from Iraq, but demand that the KRG withhold its declaration of independence until more propitious circumstances arise. Committing the Kurds to a different course risks dismantling the century-long project for which so many have perished.