If you’re thinking about applying for an intensive or clinical program for next year, learn why alumni can’t say enough good things about their experience in the Poverty Law Intensive

If you’ve ever talked to alumni of the Poverty Law Intensive, you’ll have noticed that we are almost cultishly enthusiastic about our experience in the program. The Poverty Law Intensive places students at Parkdale Community Legal Clinic for a semester-long immersive experience. Placed in either the immigration, housing, workers’ rights, or social assistance, violence, and health division, students become the primary point of contact for clients and take on the lion’s share of the work for their cases. I spent my summer after first year working in the Workers’ Rights division at Parkdale, then returned to take the Poverty Law Intensive during the winter semester of second year, and then went back yet again to do a directed reading during the fall semester of my third year. Like so many of my peers, I consider my time at Parkdale to be the most important and formative experience I’ve had at law school. Here’s why:

The Poverty Law intensive gives you the opportunity to actually practice law. Working with incredible supervisors in a supportive environment, I was given enough freedom to try my hand at developing our legal strategies, thinking through the theory of our cases, and developing relationships with clients. I drafted all correspondences, submissions, and factums for our cases, engaged in negotiations, and made oral submissions in Small Claims Court and at two administrative tribunals. At the same time, the program mentors act as a valuable resource: they let you try things on your own, but offer guidance and support, generally ensuring that you’ll never mess things up too badly if you get something wrong.

One of the first things I learned at Parkdale – much to my frustration and relief – is that exam fact patterns actually do approximate real life legal problems! Except, of course, you’re dealing with real people who are facing real problems with real, and often extremely serious, consequences. What I quickly realized is that while course work gave me some of the tools I needed to reason through the legal problems my clients were facing, those skills represent only a fraction of the work that I, as a lawyer, would be doing on a daily basis.

In the intake room, when meeting a potential client for the first time, you learn to listen and to ask questions: how does this person narrate their own story? What problems do they perceive themselves as having? Through experience, you learn to tow the tricky line between giving the person a chance to tell their story on their terms, and also getting the information you need to discern whether or not they actually have a legal problem that you can help them with. Then comes the difficulty of trying to articulate to yourself and to your client, what recourse might be available.

Lawyering is an almost unavoidably social profession. In addition to reasoning and writing, I started to develop the necessary emotional and social skills I will need in practice, and also learned to think strategically about what courses of action to pursue, considering costs, my client’s interest, and the myriad of other factors that hang in the balance for every case.

Returning to classes after a semester at Parkdale, I also found that there’s a sort of cross-pollination that goes on between experiential and classroom learning. Since Parkdale, I find I am getting so much more out of my courses because I have some practical experience to reflect on. I am continuously drawing on my experiences, thinking and re-thinking some of the things I saw in litigation, to help me understand new material.

I also learned about the limits of the law. Most people, especially when facing the many strands of hardship that come with living in poverty, have problems without easy legal remedies. Parkdale gave me plenty of hard doses of realism and hope. A lot of our clients bear the burdens of systemic inequalities, and it can be demoralizing to see client after client facing the same problems that you know have their root in some larger structural wrongs. Helping a live-in caregiver win her unpaid wages feels like a victory, for example, but it does not change the fact that her work permit severely limits her chance of finding a better employer, and that this same pattern is replicated over and over again for other workers.

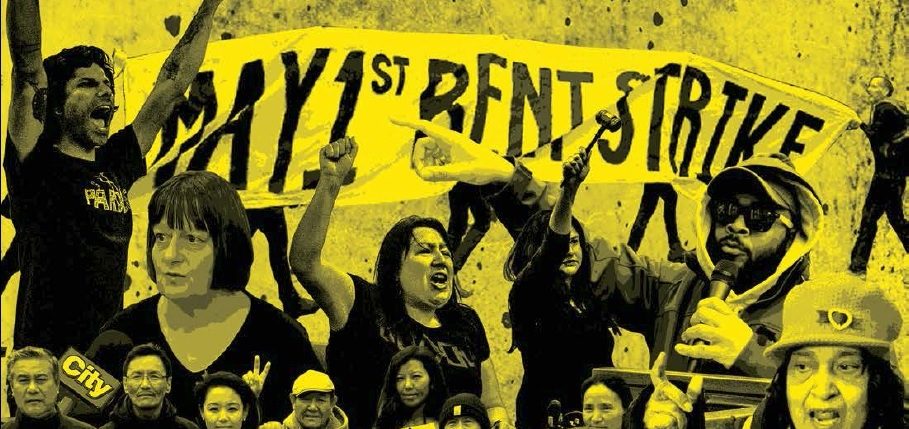

I felt continuously energized, however, by the incredible force and effectiveness of the law reform and movement building initiatives spearheaded by Parkdale’s community legal workers and community organizers. In the short time I was at Parkdale, we saw the Provincial government implement Bill 148 which makes a significant increase to the minimum wage and implements major employment law reforms; we saw Parkdale tenants win a rent strike to improve the living conditions for hundreds of residents in Metcap apartment buildings; we saw workers at the Toronto food terminal win their first union contracts for better working conditions, and so much more. In each of these initiatives, Osgoode students were there, learning from their clients and community members about how to exert people power when the law falls short of achieving justice.

If you’re interested in social justice. This, more than anything, is why I would recommend the Poverty law intensive to you. After Parkdale, I feel like I have a better understanding of how the law can be used as a tool for change, when you need to look to political strategies and movement building, and also how I could work within an imperfect legal system without being ground down by those imperfections.

At Parkdale, I also built some of my closest bonds at law school. There is nothing like learning in a community of peers who are going through the same intense experience as you. Each legal division consists of five students who sit in “pods” together. Your pod-neighbors are your first resource for legal questions and you learn a lot from hearing about their cases, almost as much as from your own. During weekly seminars, lunch hours, and after work beers, my pod-pals and I often continued to talk through what we were learning; commiserating, and reflecting on the short-coming of the legal aid system, and making plans for the kind of legal institutions we wanted to build in the future.

I also cannot say how great and supportive most of our clients and community members are. People know and respect the clinic; they know that you, as a student, are there to learn, and they are eager and patient to teach and learn with you.

People often say that law school is about learning to “think like a lawyer.” I’m not totally sure what that means, but I think that the true virtue of the Poverty Law Intensive experience is that it gave me the tools and experience to help me think like the type of lawyer that I actually want to be: someone with sharp legal reasoning skills, tactical smarts, but also a keen analysis of the possibilities and limits of the law and lawyering.