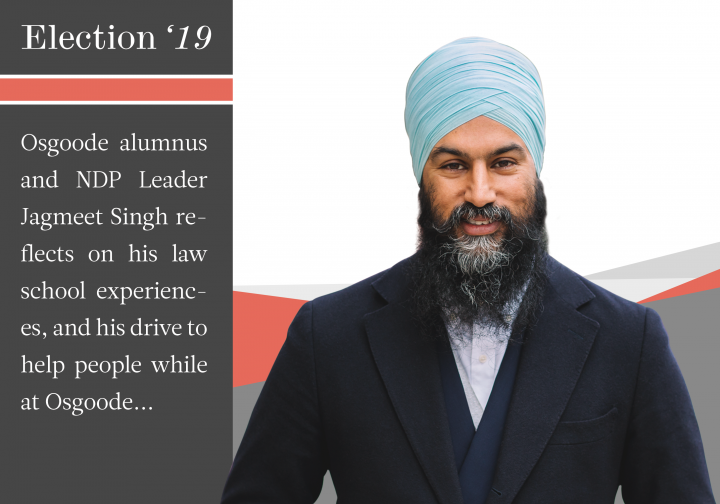

After participating in a climate strike in Victoria, BC, the leader of the Federal NDP, Jagmeet Singh, took the time to sit down and call me from the other side of the country.

Upon introducing myself as a 1L at Osgoode, he immediately wished me good luck and offered advice about the OCI process, recalling his own experience and the pressure he acutely recognized.

“I feel like what happens often in first year is … you feel like you have to go into a certain stream. But I didn’t end up getting any OCI’s and I ended up finding a whole different path,” Singh told me. “I didn’t get trapped into thinking I had to fall into what everyone else was doing, so make sure you stay open to the universe’s options as they present themselves.”

Accepting the apt advice, I steered the conversation back to Singh and got into the weeds about his own experience in law school, starting with why he decided to pursue it in the first place.

“In my life, a lot of people didn’t have the power or the knowledge to defend themselves or protect themselves,” he began. “I thought that it would make a lot of sense to give back and help out people by learning the legal systems.”

For Singh, the theme of helping out those who didn’t understand ‘the system’ or didn’t know how to represent themselves was a key motivator to going to law school. “Helping people out was always something that was a core value for me.”

Linking altruistic aspirations in law to experiences of carding

When listening, I felt that there may have been a personal dimension to what Singh was saying. So I prodded further and asked if he had any personal experiences of not having access to power and knowledge of the law. Turns out he did.

“I used to get stopped by the police a lot for no reason, and I hadn’t done anything wrong. I didn’t get charged. And I remember feeling how frustrating that was,” Singh said, recalling his own experience of carding.

I asked him whether he was able to explore issues of carding in law school. Responding in the negative, Singh described how, at that time, he didn’t have the “language around what was happening.” It wasn’t until after he graduated that he started to understand carding as a systemic problem.

At this time, Singh did not have an articling position yet and wasn’t sure of how he wanted to continue his law career. So, he would spend his time visiting the Brampton courthouse and observing issues in the courtrooms.

He recalled one instance in court where he was observing a lawyer cross-examine a police witness who had stopped a Black young adult for no reason. For Singh, the testimony demonstrated how the police still stopped youth despite having neither evidence nor grounds, based solely on the “colour of his skin.”

“Seeing that reminded me of all the times I was stopped,” Singh recounted. He explained how his own feelings resurfaced when he saw the lawyer “looking at… a trend of how police sometimes stop people not based on the evidence.” In relating the experience to his future advocacy, Singh said, “When I became [a Member of Provincial Parliament], I drew from that experience to really help me tackle the problem in a more systemic way.”

Social justice then and now: protests, policies, and prisons

Given Singh’s strong social justice focus in his current campaign, I wanted to find out what his days in law school were like, so I asked him what social issues he was involved with back then. Strongly identifying with peers who cared more about social justice than getting a job on Bay Street, Singh described his experience as a pro bono law student and legal observer at protests.

“There is a pretty strong protest culture at York where students get involved a lot, so I used to go to different events that were being held by groups that were fighting against poverty… I was involved with student groups that were protesting things like tuition fees and I helped out with groups that were helping to represent immigrants and refugees,” Singh said. “People that faced a lot of challenges were the ones that I was most drawn to and how I could help them.”

“I remember doing G7,” Singh added as he recounted one of his experiences as a legal observer. “There were a lot of massive police issues of power… almost a thousand people were arrested. And almost 80 percent of them were released without any charges, so I was there on the ground helping people, giving them legal advice or giving them support as a law student.”

When I asked Singh how these social issues connected to today, he responded by discussing continued inequality and racism in our world.

“A lot of the antipoverty work that I did… outside of law school is still really relevant. There is a lot of inequality in society,” he said. “The kind of foundation that I had, around people being treated differently just because of the way they look – that continues to be a problem, particularly given the recent blackface and brownface scandal. It brings to light that there is systemic racism, and people face that, and they suffer that, and it informs a lot of policies.”

In turning to the policies he wants to address at the federal level, Singh asserted his commitment to end carding by the RCMP and examine police services governed by federal laws.

“I want to look at the disproportionate representation of Black and Indigenous people of colour in jails and how we can stop that, develop a strategy to remedy that injustice,” he continued. “Yeah, the things that came up while I was in law school are really relevant today.”

As a law student interested in police misconduct and prison abolition myself, I prodded Singh further on this question of incarceration. I asked him whether could see a new future, a world in which jails and prisons may not exist. He responded in the negative, and instead focused on the importance of rehabilitation and restorative justice.

“So, what I have been considering is just another way, like a new way of looking at our criminal justice system … looking at how do we develop a criminal justice system that results in better outcomes like a safer world,” he said. “I think that the current approach which is a punitive model doesn’t actually make [the] community safer. A lot of evidence has shown it doesn’t. If we want to make our community safer, we’ve got to make sure our policies back up that goal, and so I would like to see us take a more rehabilitative or restorative justice approach in our criminal justice system.”

Singh asserted the need to “have a way to put resources towards helping people out as opposed to just putting them in jail”, demonstrating a recurring theme of helping others that is a key motivator in his work. He continued, “There are some people that are such a danger to themselves and to others that will need to be incarcerated, but for a lot of people, it’s not really a useful use of our limited resources.”

Singh redirected the conversation to his calls for a different approach to those charged with personal possession of a controlled substance and who often deal with a mix of poverty, mental health, and addiction.

“So those are not criminal justice problems, those are healthcare problems,” he said. “I would like to see our justice system not spend resources where we should be spending money on healthcare and rehab and addiction services instead.”

From criminal law student to criminal defence lawyer

Singh’s criminal justice policy proposals draw on some of the work he did as a criminal defence lawyer.

“I represented clients that were charged with personal possession and they didn’t need to go to jail, that wasn’t useful, that wouldn’t have helped them, wouldn’t have helped out society,” he said. “They needed help and support, and it seemed to me a really illogical approach. And to be frank, it seemed to be like a callous approach to people who needed help and support.”

When I asked Singh about his favourite course at law school, he unsurprisingly said Criminal Law, then taught by Professor Sonia Lawrence.

“I really liked Sonia Lawrence; I thought she was really cool,” Singh said. “I didn’t go into law school thinking I would do criminal defence specifically, but her class really struck me with a lot of interesting things that kind of looked at what people go through.”

He remembers learning about how the criminal justice system disproportionately impacted racialized people. “So, a lot of my later on understanding of the criminal justice system, she kind of helped lay the foundation for, which was really cool the way she kind of broke it down and I found the class really interesting.”

However, despite resonating with the material in Criminal Law, Singh reflected on how he didn’t think his path would be criminal defence until he had already graduated. He recalled his time visiting the courts after graduation and the struggles of not having an articling position.

“A lot of people would ask me, they would come up and say, ‘Hey, where are you articling?’ and I’d say, ‘Oh, I don’t have a spot yet.’ And then they’d almost take a step back and act as if I had told them I was diagnosed with a serious illness, like ‘Oh, I’m so sorry, are you okay?’” Singh confided. I couldn’t help but laugh as his experience resonated with stories I myself had heard from peers going through articling.

However, by hearing people’s stories and seeing how lawyers were able to help them out in cases of police misconduct, Singh was inspired to pursue his career in criminal law. “It was those court cases that inspired me to become a criminal defence lawyer.”

“Then I ended up calling a list of lawyers that were registered as criminal specialists by the Law Society. And I called them all up saying, ‘Hey, can I hang out with you or spend some time or have lunch with you? I’m interested in criminal law.’ And then two of them got back to me. One of them I ended up having lunch with, and then I ended up finding a way to work.”

Singh’s initial advice about seeing the path outside of OCI’s resonated with me as he recounted his non-traditional path to articling. I told him I could sense that his career aspirations were driven by what he witnessed on the ground more than what he learned in class.

“Yeah, it did, it did. It totally did.”

Parting words of wisdom

As Singh got the call from his team to wrap up, I asked him what advice he had for law students.

“Law is an amazing field of study to understand how systems work. I feel like you can’t ever have a career in law unless you think about how you can give back to the people around you… you’re never gonna feel that law is rewarding unless you find a way to give back,” Singh said.

He expanded that while you can do any area of law, it’s important to think of what brings meaning to one’s life. He continued to offer advice for law students wanting to transition to politics in the future.

“Law is a powerful way to help out a person at a time, a client at a time.” However, he continued to say that, “Sometimes you feel frustrated as a lawyer that law should be better or should be more just, and as a politician you can make those laws more just. That’s a powerful thing.”

“It’s a really great transition from law to politics because you can do the same work looking at laws,” he said, then asserting that as a politician, “you can actually make better laws”.

I squeezed in a short follow-up question about whether he had specific advice for racialized law students and those facing systemic barriers, to which he responded with the understanding that it’s tough for such students.

“I would tell people: believe in your own self-worth, believe in who you are,” he said. “You offer something unique and special to the practice, and use that strength of believing in yourself and your own self-worth to help you get through the difficult challenges that will be a part of life that we’ve got to, hopefully, one day remedy, so they don’t exist.”

On that note I thanked him for his time and wished him good luck.