Rediscovering Janet Jackson’s 1997 release in a post-Timberlake apology world

As someone born in 1998, I was far too young to have any vivid memories of the 2004 Super Bowl (yes, Tom Brady and the Patriots won that one too), the halftime wardrobe malfunction, or the immediate panic that it sparked. However, the subsequent cultural framings of the event have lasted throughout my childhood, and served as an early cautionary tale about the consequences of being hypervisible and Black. The race and gender dynamics at play in the aftermath of the incident are unmistakable. For an incident that lasted for nine-sixteenths of a second, Janet Jackson was portrayed as a promiscuous attention seeker, a puritanical scapegoat for all societal ills and taboos and was blacklisted from numerous media institutions. Justin Timberlake meanwhile, whose career can be attributed to his proximity to, and ability to feign Blackness, was able to ascend to new levels of celebrity post-malfunction, and even had an about-face at the 2018 Super Bowl.

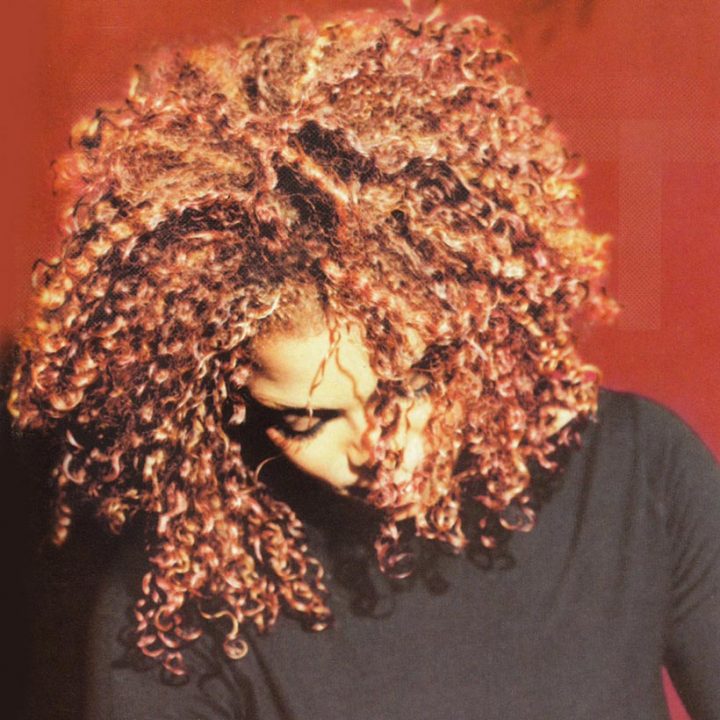

Therefore, it feels like a depraved, cosmic joke that Timberlake’s apology for allowing Janet to take the brunt of the criticism is 1) seventeen years late 2) written on the Notes app (?), and 3) hastily tacked onto another apology for the misogynistic mistreatment of another hyper-criticized popstar. For someone who was omnipresent throughout the 80s and 90s, it’s disheartening to see Janet’s artistry reduced to a cultural footnote today. In the spirit of Black History Month, it is imperative to give Janet her flowers by revisiting her groundbreaking 1997 release, The Velvet Rope.

From The Velvet Rope’s outset, we are invited to “step behind the velvet rope”, to access and unpack Janet’s once-guarded ruminations about grieving, liberation, and finding intimacy in an increasingly digital world. The driving force behind all of these meditations is Janet’s sexuality. Suggestiveness has always been a part of Janet’s value proposition as an artist, but The Velvet Rope sees Janet reach unexplored heights. She sings candidly (and quite explicitly) about sexual intimacy on “Rope Burn”, offers blatant condemnations of homophobia on the frenetic “Free Xone” and even turns Rod Stewart’s uber-heteronormative “Tonight’s The Night” into a ballad about same-sex yearning. For an artist with her cultural cache to devote their artistry to LGBT rights and queer relations only several years removed from the HIV/AIDS moral panic is remarkable.

This thematic boundary-pushing extends to the album’s rich sonic palette. From the electric violin riffs on “Velvet Rope” to the distorted bass synths on “Go Deep”, The Velvet Rope’s production is multi-layered and dense throughout. This is exemplified on the surreal and forward-thinking “Empty”, in which its staccato drum loops and lush harmonies would be right at home on an FKA Twigs or Jai Paul project today. With help from the legendary production duo, Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis, The Velvet Rope traverses numerous genres seamlessly. Janet transitions from SWV/Jodeci-esque slow jams (“Anything”, “I Get Lonely”), to raucous, speaker-rattling funk (“What About”, “You”) at a moment’s notice, with her highly malleable vocals scarcely feeling out of place. Standout track “Got ‘Til Its Gone” is a neo-soul/jazz-rap fusion where Janet’s former on-screen boyfriend Q-Tip floats Joni Mitchell samples and J Dilla record scratches. The Velvet Rope reaches its pinnacle when Janet reaches into her electronic/house bag and wholeheartedly embraces her “Rhythm Nation” roots, which she does on “Together Again”. A contemporary pop radio staple during my childhood, “Together Again” sees Janet deliver heartfelt and optimistic meditations on a life lost over pulsating house rhythms.

The Velvet Rope is essential listening in a post-Timberlake apology world because we ought to make our support for Black women at the receiving end of structural harms explicit and lasting. Whether it be through #justiceforjanet or Clubhouse rooms devoted to making Timberlake “answer for his crimes”, it’s good practice to incorporate critical race lenses into how we interpret and unpack celebrity. What is always missing from the cyclical discourses about the wardrobe malfunction, however, is appreciation. From Anti to CTRL, Janet’s fingerprints are undeniably all over the pop and R&B that we consume today, and yet we consistently fail to ascribe the appropriate magnitude to her work. The onus is on us all to ensure that Janet’s artistry takes precedent over the incident that has unfairly defined her.