all it by whatever moniker, the urbanist movement is strong among young people worldwide. I share many sympathies with it, of course: who doesn’t want better, more walkable spaces with readily accessible and convenient transit? I’m a frequent passenger of provincial commuter rails, coaches, and the good old TTC myself. I’m glad our province and its cities are embarking on such ambitious transit projects. As much as I dislike the traffic delays, I am immensely proud to see new railway infrastructure connect our capacious Ontario.

So, I don’t really have as much a qualm with urbanists. As a matter of fact, we share a lot of common ground. But a persuasion held by some that I’ve always staunchly disliked is the opposition towards cars. Cars have long borne an ill reputation for a slew of issues, but the stripe of rhetoric most prominent today seems to have been the most existential for the automobile. As pedestrians, cyclists, trams, buses, and trains all compete for the same length of asphalt and gravel (to say nothing of the endless ammunition offered by environmentalist and safety interests), the availability of cars has been thrust into troublesome straits.

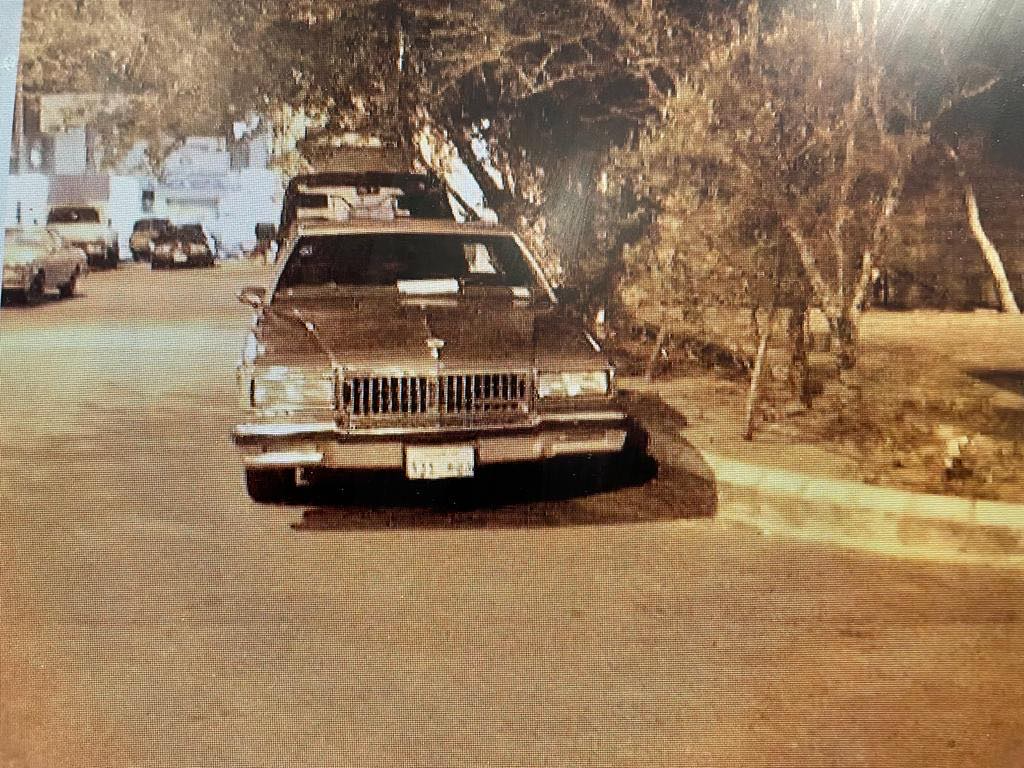

I’m a longtime gearhead myself. It’s not uncommon—no matter where you are in the world—to come up as a kid who plays with little diecast models and racing video games and enjoys an emotional attachment to a succession of family cars. There’s an incredible sentimentality to the whole thing. When you get older, driving and getting your first car become landmark rites of passage towards adulthood. I remember the first time I was behind a wheel: much too young to drive, no less to operate a manual. I was eight years old, and my family had road-tripped down to the Red Sea Riviera on holiday in our little black Daewoo Nubira. I asked my father for a chance to pilot, and was granted the dubious but always illustrious honour of the first parking lot drive. Even on a wide, dead-end road, I could barely get the thing going. I kept stalling the family Nubira on every attempt: I just couldn’t push the clutch in right. It wasn’t a perfect drive (in fact, the only perfection to it was the flush of stalls I pulled that day), but it is a perfect memory.

You’ll mind that the digression may seem beside the point, but to me, it is the point. I’d rather not write a diatribe about why this or that point is incorrect because of fact so-and-so, because the truth of the matter is that cars are risky and they can be unsafe. But what few pleasures can we enjoy without risk? What sparse a class of endearing things there is, besides that much adored four-wheeled machine. No bean counting nor “assessment of societal risk” will ever detract from the chamber of mental freedom that the car offers. You can make a million and one arguments about why they’re great too, but why bother listing them? You’re always going to define why a car is special to you in completely subjective terms. It could be that a car is a time machine for past moments of which you’re fond, or that you enjoy going anywhere with it in the present. Perhaps it’s your personal space, where the world becomes faraway, and serenity awaits behind just one shut door and a stereo knob.

When first putting this piece into concept, I thought about making it the usual platter of arguments about why we should preserve something despite its downsides. That can be interesting on its own, I suppose, but in the process of penning these words, there was a revelation. I hardly need a sterile thesis to say why the car’s special and ought to be preserved. You don’t either. It’s never point A to point B. The car is precious. It might be demanding in cost—in more ways than one—but we will always need everything it offers, especially the memories.