Sam Peckinpah is the sort of director that proves the trope of distinct creative genius as a product of erratic and troubled people. Perhaps some would be amazed that self-loathing and alcoholic idiosyncrasy could be such a strong conduit of filmic success—but if you know great artists, you know that eccentricity is raw material for much brilliance. Peckinpah’s career as a filmmaker was longer than most, but shorter than some. His deeply troubled process—and the miracle that was his ability to somehow continue securing major studio funding—left a rather illustrious trace of reels over two decades.

Many of these productions give little charity to a reductionist “drunk director” persona associated with Peckinpah, marked by his infamous self-admitted observation that he “cannot direct while sober.” The obverse of that story reveals his less sensational character—softspoken, intelligent, and artistically responsible: Hardly a blowhard coke & whiskey addict. This revisionism never made for an especially good tabloid, but the quality of his works speaks more timelessly for Peckinpah than any dated magazine feature could.

Some of his movies are so big they need no introduction, or only a mere reintroduction to newer generations. Other works evoke only passing nostalgia or the pretensions of fans drawn to obscurity like archaeologists to amorphous artefacts. What I self-importantly declare the “Peckinpah Suite” is a collection of essential, interesting, and wildly overlooked movies that any entrant to the director should see as a sort of supreme sampler to this landmark filmography. Think of it as an “Essentials” album: A little bit of everything, compressed and curated, and above all the best representation of a unified artistic vision.

Major Dundee (1965)

Before The Wild Bunch etched in lightning a legacy of cynical, pulpy violence that made his work a benchmark of American cinema, there was Peckinpah’s botched masterpiece in Major Dundee.

The film’s namesake is its eponymous fort commandant, who oversees a tired, faraway frontier outpost and POW camp for Confederate prisoners in the latter years of the American Civil War. This undesirable assignment isn’t exactly a volunteer post, and that some misdeed or disobedience won Major Dundee this administrative exile is not lightly implied. A yearning for the field veiled by a sense of mission leads the Major to assemble a posse of local gunfighters, troops from the fort’s garrison, and a forlorn hope of Confederate prisoners conditionally readmitted into service. Included among them is an imprisoned Confederate officer with whom Dundee shares a long, troubled history and rivalry dating back to their days as colleagues in the Antebellum army. This motley force campaigns along the Rio Grande and down into Mexico in pursuit of an Apache chief & raiding band responsible for an attack on homesteaders and Union troops in the western theatre. The troubled missions and contradictions of its prosecuting force becomes the fodder for a desert epic more modest in scale than Lawrence of Arabia, but just as invested in the grandeurs and struggles of journey.

For a work without Peckinpah’s latter day matured style, Major Dundee was a forerunner for everything his films would recurringly explore: His sentimental endearment towards Mexico, tragically aborted romances, violently alcoholic characters (perhaps a vessel for introspection), and incomparably distinct action—rapid cuts, close-ups, chaos, confusion, clouds of dust, emphatic slow motion, overwhelming screams, and & punctuated blood. Dundee is markedly less bloody, but still violent with appropriate reserve for 1965—Hays Code-era censors objected to the graphic grit of this epic on the Rio Grande. Today’s appetites would hardly find it as scandalous, but Peckinpah had that gift of prescience in the form of this overlooked western that was reinventing both the director’s own style and parts of the genre back when outsider Italian filmmakers were the ones on that advance guard.

Dundee’s production became infamous for the typical ambition marred by alcoholic incapacity that—exaggerated as it may be at times—held true for Peckinpah shoots in 1965 as it did for those in 1976. When at last put together, studio meddling forced a re-edit onto Dundee that left its original vision stillborn. Peckinpah ended up disowning it, but a posthumous restoration and recut of Dundee repaired the picture to its closest artistically intended form. Today’s audiences can enjoy Dundee with purer leisure: As an early hurrah and harbinger of Peckinpah’s many great works. That doesn’t rewrite the movie’s history as an artistic and commercial failure at release, but it does let us peer into a more linear throughline of how Peckinpah drilled his craft for years before he found incredible runaway success in The Wild Bunch. While unideal as a starter delve into Peckinpah’s work, it’s a western epic more than worth its runtime & is bound to become essential viewing after you’ve flipped through his more refined (and complete) projects. Just make sure to not to get it mixed up with Crocodile Dundee when you’re at the video store.

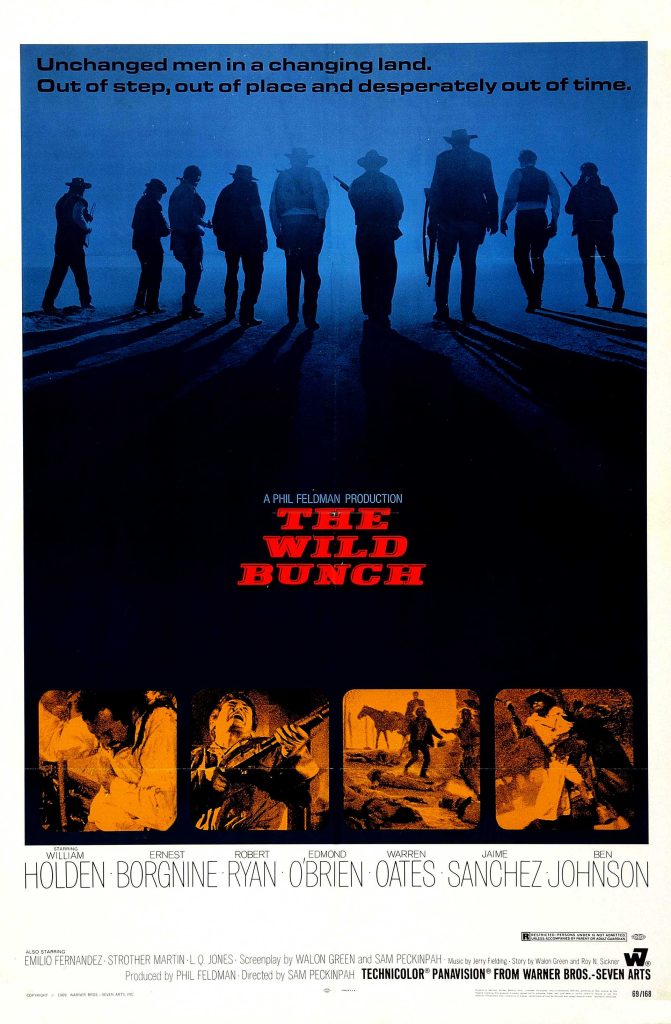

The Wild Bunch (1969)

No talk of Sam Peckinpah is ever without mention of The Wild Bunch, an accolade paid in gallons upon gallons of film blood. A consummate revisionist western that dances on richly troubling frontiers—the Mexican-American borderlands & the end of the romantic banditry of the open West—The Wild Bunch is the most influential and notorious product that the director ever put out. Many an essayist has sketched why The Wild Bunch is so important in much better prose, so I elect to contain myself to its place in Peckinpah’s cinema.

The opening bank heist & ensuing massacre is all that’s quite needed to set The Wild Bunch’s tone. Fittingly set in 1913, the leading gang is the typical ensemble of cowboy bandits, but with a much colder and sadistic edge than many previous iterations of the sort. Perhaps consolably to us, this form of banditry is also outdated—even pathetic—by the time Colt .45 revolvers were being traded in for Colt .45 automatics. After the heat turns another raid into a fugitive escape, Bishop’s Gang cuts down to Mexico (sensing a theme?), and enters the employ of a counterrevolutionary general lording over what spoils he could pilfer from the country’s civil war-stricken fiefs. Opposite this, a former member of Bishop’s Gang—Deke—helps the railroad barons and local law in tracking down his former partners in crime on the threat of renewed imprisonment—a reluctant Judas operating not on bounty of silver, but danger of Roman sword. Intrigue, camaraderie, and a numbering of days surely follows in one of Peckinpah’s most anti-heroic and fluent cinematic works.

The director’s signature muddled morality and gratuitous violence—quite revolutionary in its depiction of graphic violence for the time—has left The Wild Bunch as the most hailed of revisionist westerns, and perhaps the genre’s most dramatic departure from the traditional binds of its more classical style. Ironically, for as much as westerns are my favourite genre, I’ve often thought Peckinpah’s other works surpassed The Wild Bunch. Maybe my interest in the more personal aspects of his filmmaking has spoiled my eyes to the greater, more general quality that The Wild Bunch offers. If nothing else, though, it was my introduction to the director, and it often is for many a viewer who’s more likely lured by an exceptional, defining benchmark than lesser-known films. In that way I think The Wild Bunch is the best starter to the “Peckinpah Suite,” but its fame has ironically lessened the director’s ownership over its themes and characters, which now lay in more revealing wait in his obscurer movies. You should see The Wild Bunch in any case, heeding both its historic importance as the one of the greatest westerns ever made, and part in the Peckinpah canon. To watch it in isolation or without further context would be to collapse the greatness of the picture and its director, affording a pittance of the warranted credit to either.

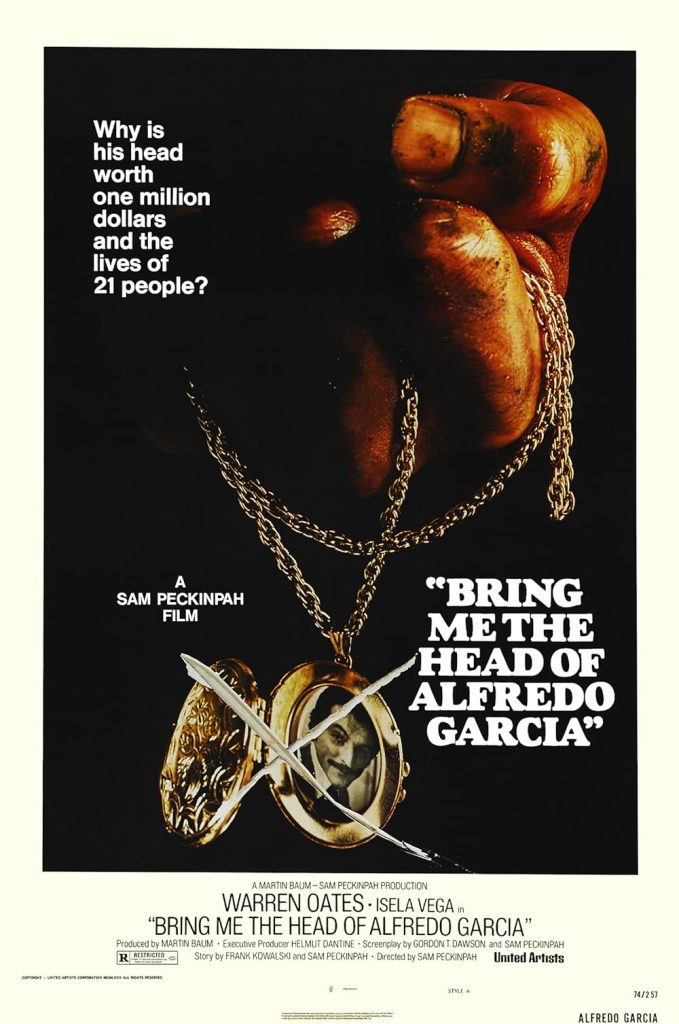

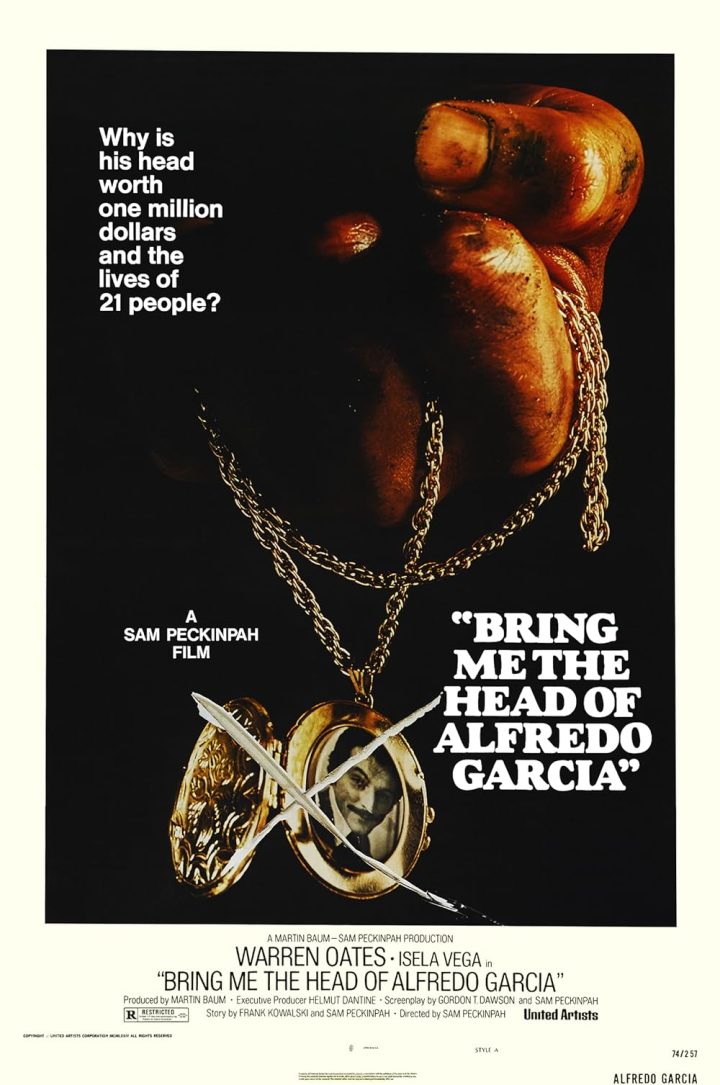

Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia (1974)

The second time I watched this movie was at a Revue Cinema screening presented on original 35mm reel. It was safely more enjoyable than the typical isolation offered by the humming Blu-Ray player host to most of my screenings. It’s also a different species of viewing to watch a classic with an audience, a form of alternative perspective by collective osmosis. Alfredo Garcia was a lot funnier than I remembered—what with its grotesque and grimly mocking sense of humour. An engaged public, even if it was a very narrow demographic of film nerds, more than lifted this often forgotten neo-western through its cheers, laughs, and jeers. When I look at it after my second viewing, I see how this film’s more understated production and story came to mirror the struggles Peckinpah was trying to reconcile in what is by far his most personal movie. But I suppose that to open your heart is to invite misunderstanding, and for the longest time Alfredo Garcia was seen as a misfire long afield of the bullseyes Peckinpah hit in previous works (chiefly The Wild Bunch, The Getaway, and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid).

To its detractors’ credit, Alfredo Garcia is a lot less grand than something like Dundee, or even Peckinpah’s later lorry adventure in Convoy (1978). There is, though, much to impress in the economy of Garcia. It may be straightforward to think thrift a companion of narrow creativity, but this more modest production is still a bold cross-country hunt laced with exciting shootouts and an incredible underlay of vice. What Alfredo Garcia suggests or shows in modicum is oft more impressive than if present fulsome. Take some of its elements: The grand hacienda from which the powerful Don (who sets the plot in motion) visits misery onto many beyond his sight, the consortium of assassins—warped New West prospectors—mining a dead man’s name for the price on his head, & the rustically impoverished pueblos by via which opportunistic hitmen transit as they disturb stones intending to remain unturned. This is the one Peckinpah film best left described only in cryptic generalities than sweeping synopses.

Like all Peckinpahs, it ends with a flurry of violence, but here it’s carried with a more personal and emotional ballast courtesy of the director’s self-insert as the leading man. The cinematography throughout gives a more sickly, sun-bleached decay than even the most scorching of his desert settings. For one of his most overlooked works, Alfredo Garcia is the most stylized and invested of all his pictures. Within its fifty years since release, this film has finally been attended by some due, but it often remains a companion of the obscurity in which it has long waded. Such a condition makes for the best recommendations, for if nothing else it extends long awaited courtesy to the works for which its artist cared so deeply, yet for which the only reception has been cold neglect.

Cross of Iron (1977)

It’s not uncommon to rate Alfredo Garcia as Peckinpah’s last great work, but Cross of Iron contends against that point and then some: It may be his greatest work altogether. It wasn’t his last movie, nor was it his most popular or most celebrated. As unconventional as it first appears by Peckinpah’s previous standards and trappings, Cross is a frontier movie: Literally—in its warring frontiers of the Ostfront—and thematically—via the frontiers of weariness, tragedy, and moral destruction that follow its warring armies.

It’s often said that the greatest tragedy of the anti-war film is its innate thematic defeatism. War lends itself well to exciting action. Perhaps this maxim is best discussed in a treatise other than this, as all that one can say of Cross of Iron is that it does not contend with that excitement whilst maintaining its anti-war edge. Led by a sardonic yet troubled James Coburn performance—possibly his best role—the grimness of the most savage front of the Second World War hosts a class war on the Kuban. The story focuses on a jaded, veteran sergeant, Steiner, fighting during the onset of the most futile days of the German Army on its most significant front. Much of the story revolves around the friction between himself and a newcomer aristocrat captain (played by Maximilian Schell) who is little more than an opportunist, requesting transfer to the Eastern Front from his cushy post in Occupied France only so that he may chance to win a medal: The Iron Cross. Steiner, highly decorated himself, holds nothing but disdain for the glory hound officer, with no love lost by the Captain either. The plot sometimes paces away from this core friction, but Steiner always remains the thematic anchor by which Peckinpah documents his superb portrait of the highest echelons of violence. Indeed, one of the movie’s standout scenes is in a military hospital isolated from the main story & the frontlines, yet arguably the most visually stunning and impressively scathing centerpiece in the whole picture.

Cross is a narrative as deeply personal as it is grandly thematic. Peckinpah’s graphic violence is most at home in a setting where senseless violence is at its most banal. One thinks, in fact, that this is an epilogue for the sort of stylized shoot-outs for which Peckinpah became famous. The director long struggled with the fact that audiences enjoyed his gratuitous violence as voyeurism, and not with the critical catharsis that he intended. This is what arguably renders Cross the most shocking and drearily violent of all his works. Peckinpah finds an equilibrium in his philosophy of violence. Scoring the point are opening and closing montages that are not only masterworks of editing (many other WW2 films from around the same time used similar montages, but much more flatly than Cross) but colour the bitter irony that threads throughout the work. Cross may in fact be worthy of more than the honorific of “last great film” by Peckinpah—it’s a strong contender for the finest work he ever put out. It neither lacks in its acting or production value. It has a unity of vision and artistry clearly aged from a trail of the experimentation and lessons Peckinpah derived from his previous movies. Orson Welles once endorsed it as the greatest war picture hitherto made, after only All Quiet on the Western Front (1930). Watching it today, and with the hindsight of all Peckinpah’s previous films, renders Welles’ praise rather understated.

Coda

Peckinpah was hardly sedate in his directorial style and on-set presence. This became the stuff of rather particular legacies: One as a leading herald of stylized, cinematic violence in America & another as a troubled artist wedded to the bottle. What’s in a man’s name is often more complex than what a reductive reputation lets on, though. One of my article’s follies is that it’s also a bit of lightly concealed apologia. Sure: I would like you, the reader, to be introduced to a couple gems of cinema that I think most would enjoy, and by extension give further lease to the reputation of a filmmaker whose modern fame has somewhat languished. Yet I also write in retort against the characterization of Peckinpah that’s long haunted his mention. Any modern viewer looking to read more about him, watch his interviews, or learn of his person is bound to cross with the archetype of the degraded drunkard which finds Peckinpah like a picture in a dictionary. I think in appreciating the nuance of his film record—which some audiences and critics have not been as kind to too either—there’s much to say about the shades of the man himself. There will always be truth to Peckinpah’s dysfunction, but look deeper into his movies and there’s something that speaks more subtly to what he was about. That, to me, will always be the stuff of more enduring legacy.