Last week, Robyn Schleihauf published an article in the Obiter, condemning Trinity Western University’s (TWU) highly politicized application for accreditation of what could become BC’s fourth law school. She describes TWU’s Community Covenant as a “national disgrace,” proponents of which ignore “an underlying misconception: that requiring gay people to suppress their sexuality is not discriminatory.”

I’m gay, by the way, and I’ll definitely get push-back from my own community on this one. Not to worry, I’m used to it by now. I’m extremely pro-gay rights, pro-gay marriage, and all the rest of it. I have been “out of the closet” since eleventh grade, and coincidentally, grew up in Kelowna, a small BC town much like Langley (where TWU is situated). I’m also a fervent agnostic, somewhere on the borderline of atheism. I’ve often had impassioned, but respectful debates with religious individuals.

I agree with Ms. Schleihauf that the covenant is quite ridiculous. But I do question certain arguments she posits, and have arrived at a somewhat different conclusion. Here are a few of Schleihauf’s key points, and my responses.

1. “Private institutions allow for a greater amount of opportunity and choice for those who can afford it.”

Rock on. I don’t see how this is a bad thing. The world’s finest universities: Harvard, Yale, and others are private institutions; Harvard students whose family income is less than $60,000 pay no tuition at all. Of course, TWU is unlikely to become the Harvard of Canada; at least one would hope not. As for Yale, its shield still features the Bible, with Hebrew script, a testament to the school’s religious roots.

In a free society, opportunity and choice are considered virtues. Canada has a rather strange national trepidation for private alternatives to public services—a good example is the perennial ruckus over two-tiered health care. We’re one of the only countries that tries to outlaw this apparently nefarious practice. In other developed countries with public health care schemes, the two-tiered model usually works just fine. There’s a market for private health care in Canada, and private hospitals are slowly popping out of the woodwork. Wealthy Canadians, including the former Premier of Newfoundland routinely escape to a US hospital for medical care. No laws or regulations can stamp out high demand for a product or service—consumers will find sources of supply somehow: legally or illegally.

2. “Where law school tuition is already a run away freight train, private institutions could have the effect of driving our tuition costs even higher.”

Really? I doubt anyone can substantiate this inference. I’d like to point out that TWU and other private universities do receive some public funding through the federal “Knowledge Infrastructure Program.” Personally, I think this funding should be revoked. Nevertheless, this funding is a relative pittance; most is provided by private donors. By ushering students into TWU, doesn’t this leave more funding available for the rest of us who attend mainstream, public law schools? Isn’t high tuition an enduring qualm amongst Osgoode students—I recall a recent panel held on this subject.

Ontario has no problem funding its Catholic school system. I’m not okay with this either: I’d agree with Schleihauf that government should not fund religious-based institutions. But here, the Catholics are protected by BNA Act, and our collective exhaustion on the topic of constitutional-amendment remains, even two decades years after Meech and Charlottetown.

3. “To allow one moral viewpoint to have priority over others, particularly in a legal education context, is not preferable to a system that arguably allows more space for divergent or minority opinions.”

On this point, I agree completely. Social sciences and law revolves around accommodating and debating different viewpoints. Law students and faculty are quite intelligent, as we all know. I agree that most of us are able to decide things for ourselves, without the need for “intellectual protection.” Many of the professors I’ve admired most in my academic career have been those with completely divergent opinions. As an undergrad in Political Science at UBC, it was extremely enjoyable and thought-provoking to attend a class taught by a fervent Marxist, followed by a lecture from an ardent Neoliberal.

I’m an agnostic, and I have a distaste for religious dogma. However, my distaste for censorship is equally strong. Progress in human history has been propelled by exposure to viewpoints that were, in their time considered radical. In my opinion, TWU’s covenant is blatantly discriminatory and antiquated. But there are those in this country who believe in such principles, as is their right. It is at this point where Shleifhauf and I part ways. Are we sure we want to deny this minority community a forum for legal education? Isn’t this the very crux of Shleifhauf’s above-mentioned argument? Denying the TWU proposal would likely result in anger and outrage in the religious, conservative community–just as the LGBT community continues to take to the streets to demand their civil rights south of the border. This is the last thing we want to see—renewed acrimony between minority groups that have never really seen eye-to-eye.

Schleihauf proceeds to rhetorically quip (of TWU’s religious doctrine): “Ought law students and faculty to be protected from being exposed to viewpoints that might offend them?” But a brief perusal of our school’s website, or a simple gaze around the halls would indeed reveal that Osgoode itself also adheres to a dominant moral viewpoint, endorsed and promoted by the school. I’ll call this viewpoint “secular social liberalism.” One tenet espoused by this doctrine is needs-based benefits, exemplified by Osgoode’s means-tested bursary program, which in essence denies funding to many older students. Second, applicants are meant to “personify the spirit of the Law School through their diversity” (from the Osgoode website). Thus, like most other schools, Osgoode has a distinct “aboriginal” applications category (in addition to other benefits for aboriginal students), and offers a waiver for many mature students who do not hold an undergraduate degree.

Not everyone would agree with some of these “preferable treatment” policies, which may deprive some equally meritorious candidates of an offer of acceptance. I am not condoning or condemning these policies here, but simply making the point that most Canadian law schools operate under this particular dominant moral viewpoint. Business schools, including Schulich, do things a bit differently. TWU is proposing an alternative, call it “Christian social conservatism” if you will. We can certainly criticize the moral imperatives dictated by TWU’s Covenant, but who are we to censor them completely? Students should be given the right to chose the lens through which they study law, even if the mainstream profession finds the approach questionable.

History has shown that attitudes change over time, and time is on our side in this matter. Forcing groups to adopt new systems of morality has usually resulted in epic failures. In the case of the LGBT community, (which the press seems to focus on in this case) we have one minority jousting with another. In essence, whether visible, invisible, cultural, political or linguistic, we are all minorities in some way. The sooner we begin to agree to disagree, and attempt to live harmoniously despite our differences, the better.

TWU won on its accreditation for its Teachers College at the SCC in 2001. We’ll have to see how episode 2 plays out, as Mr. Harper has consistently taken his nail file to the left side of the bench, gradually tilting SCC to the right with his appointments. With the retirement of the revered Justice L’Heureux Dube (the only dissenter on the TWU #1 case), Justice Abella seems to be the last remaining left-leaning judge on the court. This suggests that the court may be loath to distinguish TWU #1. Justices Iacobucci and Bastarache declared the argument that “graduates of TWU will act in a detrimental fashion in the classroom is not supported by any evidence.” This ruling effectively permitted discriminatory beliefs in private education under s.2(a). I think TWU will win again in round 2—after all, what’s the difference between a teacher and a lawyer? A lot, actually. Teachers shape the minds and attitudes of young, impressionable children—these are the students in need of intellectual protection! Their accreditation, to me, is more controversial than for lawyers, who are meant to silence their personal views, and defend even Lucifer in the name of his right to a fair trial.

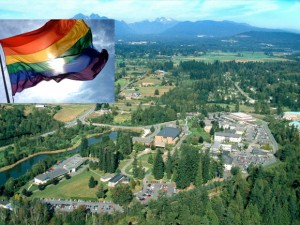

I contend that the outrage and attention we’re all giving TWU is exaggerated. Most of us would agree that the Covenant is overbearing and discriminatory. Let it be known that I would never attend TWU, though it does look like a pleasant place from the pictures. For some, that might be appealing—sans power lines running through campus! But I doubt many star legal scholars and prospective students would abandon UBC and UVic to take up residence in pastoral Langley.

I think the best way to approach this is to ignore the school, letting it fester in its obscurity and insignificance. Let it become a running joke—Canada’s legal equivalent to the University of Phoenix. But so long as my tax dollars aren’t used to fund it, I won’t be protesting in the streets.