Allow me to open this article with a rather trite statement: judges and courts play an important role in the development of the common law. Their interpretations have wide-reaching influence, from determining the approach of lower courts in the future, to affecting how lawyers advise their clients. This effect is amplified in the Supreme Court of Canada, where only a relatively small number of cases are heard each year.

Though their relevance is obvious to anyone with more than a week of law school behind them, we tend to give much less thought to the implications of the position and power common law courts hold. If we acknowledge that the decisions of the court have a direct effect on how the law functions, then one of the things we ought to consider is how judges are making those decisions. To put it otherwise, we should look to the patterns of reasoning that emerge when we consider a broader range of cases, and ask ourselves whether that reasoning is the kind that facilitates a coherent, straightforward and fair development of law.

These are exactly the kind of concerns that underpin the legal functionalism/formalism debate. Legal functionalists abhor the separation of legal reasoning from policy considerations, a distinction that legal formalists cling to. Rather than relying on abstract principles, functionalists urge judges to undertake the process of decision-making by reference to social facts. Though certainly not the first to espouse functionalist ideas, Felix Cohen contributed what is perhaps the most colourful rejection of formalism, writing of “the heaven of legal concepts”, where lawyers could squeeze an infinity of meanings from a single statute and divide a hair into 999,999 equal parts.

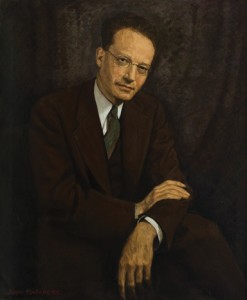

One of the most significant American legal theorists of the twentieth century, reading Cohen’s biography is an exercise in humility. Earning his Bachelor’s degree (magna cum laude, of course) before he was nineteen, Cohen went on to earn an MA in Philosophy from Harvard by the time he was twenty-one. He began work on his PhD immediately after, and entered Columbia Law School to simultaneously pursue his LLB. While you were binge-watching Breaking Bad, he spent his midyear break at law school passing his PhD exams, earning his doctorate when he was twenty-two, and his law degree shortly after. His career accolades, though too numerous to list here, include drafting legislation in the Solicitor’s Office of the Department of the Interior, heading the offices of major American law firms and teaching at Yale Law School, City College of New York and Rutgers Law School.

Cohen’s rejection of the “transcendental nonsense” of legal formalism was unwavering and influenced many to come. He held that legal arguments cannot be made by simply referencing other legal principles, since both are ultimately fictions. We can’t say (as the court did in International News Service v Associated Press) that something should be considered property because it has market value, because something has market value only if a legal system already recognizes it as property. This sort of tautological reasoning, said Cohen, was endemic to the formalist approach and resulted in courts making incoherent, indefensible and plainly incorrect decisions.

Rather than working exclusively within the confines of legal theory, without reference to contemporaneous developments in other areas of research, Cohen saw himself as part of a broader movement, one which extended to the disciplines of mathematics, physics and philosophy. In the last of these, the sort of approach Cohen was advocating was embodied by the logical empiricist movement. This school of thought sought to regulate the practice of philosophy so that it mirrored the rigour of the scientific method. Pursuit of this goal was taken up slightly differently by different proponents of logical empiricism, but its most notorious embodiment was the verificationist school, which held that the meaning of a statement is only equivalent to its verification; statements were only meaningful if they could be verified via empirical observation. As a result, any and all areas of philosophy that did not take as their starting point empirical, verifiable observations were, quite simply, nonsensical. On this reasoning, many of the things debated in fields of aesthetics, ethics, philosophy of religion or any other discourse that took as its starting point anything less than testable premises were pseudo-problems. The idea was that if philosophers wanted philosophy to be taken seriously, it had to proceed in the same way that science did: on the assumption that everything is revisable, and that things we take for granted as universal “truths” can only be regarded as such until they are disproven. This sentiment was undoubtedly influenced by nearly-contemporaneous advances in physics, like the theory of relativity, which radically changed how we understood space and time.

Cohen’s ideas can be situated in that tradition. Rather than building legal arguments by making internal references to other legal fictions, we should look to the implications legal decisions will carry for social reality. Things like rights in rem or corporations only have meaning insofar as the law says they do, so to base a legal argument on one of those ideas is to make a circular argument. Instead, we need to conceive of legal reasoning as focusing on the relations between the decisions a court makes and the consequences they will carry. Once we do so, Cohen argues, we choose the decision that is most likely to carry the most desirable consequences. In order to determine what makes a consequence desirable however, courts will have to takes sides on contentious social, economic and political issues. The discomfort they feel in the wake of having to do so is one of the things that pushes the judiciary, so says Cohen, towards formalism.

Although the ideas put forward by the logical empiricists sound attractive, many are quick to point out that problems do emerge. To name one of the many objections that have been made, it has been argued that logical empiricism fails to accurately mirror how science actually develops. If we take seriously the idea that everything is revisable, we might as well pull down the entire scientific framework each time we answer a question on a lab report. But of course, this is not how scientific theory plays out in practice: we don’t test Newton’s laws, but rather, we deploy them. If we build a bridge and it falls down, we don’t assume that something must be wrong with Newton’s laws, but rather we figure that we must have disobeyed them.

Could a similar argument be made in the context of legal functionalism? The sort of picture that Cohen proposes seems to leave little room for pretty foundational ideas, without which we would have to reformulate how we think about the common law itself, like that of stare decisis. If courts are to make legal decisions based on the consequences we expect them to have for social reality, and if courts are not to base their arguments on other, abstract legal concepts, then are we to abandon all deference to the decisions of higher courts? Is this really the most efficient way to build a legal system, that each time we are faced with a problem, we start at square one?

To be sure, the sort of legal functionalism that Cohen proposes has it strong points. But one might wonder whether, when taken to its logical conclusion, the way in which the functionalist method would play out in practice is not entirely unproblematic. The question, then, is how to find the balance between the sort of circular reasoning and appeal to transcendental nonsense exhibited by the formalists, and the perhaps impractical implications of a staunch adherence to functionalism.