A story of Ukrainian refugees seventy years later

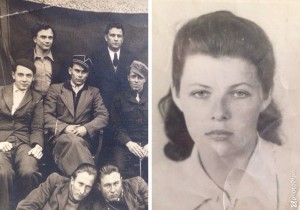

At the end of the summer, just before returning to classes at Osgoode Hall, I made my annual summer trip to my hometown of Winnipeg. While there, I visited my Ukrainian Baba, and came across the following two photos. On the left is a photo of my Dido in a refugee camp in 1944, alongside other Ukrainian refugees. On the right is my Baba in 1945 in Hanover—this was the identification photo she had to submit in her refugee application to come to Canada.

At the end of the summer, just before returning to classes at Osgoode Hall, I made my annual summer trip to my hometown of Winnipeg. While there, I visited my Ukrainian Baba, and came across the following two photos. On the left is a photo of my Dido in a refugee camp in 1944, alongside other Ukrainian refugees. On the right is my Baba in 1945 in Hanover—this was the identification photo she had to submit in her refugee application to come to Canada.

My grandparents were among the millions of Eastern and Central European refugees that fled ahead of the advancing Red Army, desperately trying to reach the America, British and Canadian armies before Stalin cut Europe in half and threw a 45 year Iron Curtain over the East. As anti-Communist, Ukrainian nationalists, my grandparents would almost certainly have been killed if they had been unable to escape the Soviet Union’s reoccupation of the Ukraine. They fled from city to city in a cattle car, so crammed with suffering humanity that it was impossible to sit down during the journey. Eventually they reached the Western Allies, from where they applied and were accepted as refugees to Canada. They eventually settled in one of Canada’s great Ukrainian communities in Winnipeg’s North End. They were not the wealthy, hyper-skilled immigrants privileged by our current policies–my grandfather became a bricklayer and my grandmother was a night cleaner in corporate offices.

If you are reading this you have likely noticed my incessant and insufferable hectoring on the Syrian refugee crisis, posting articles and raging inelegantly against those defending Canada’s current immigration and refugee policies. My annoying insistence on highlighting the plight of the Syrian refugees stems from the personal resonance I feel on this issue. Quite simply, if Canada in 1945 had had the restrictive quotas and burdensome bureaucratic requirements of today, my grandparents would never have made it here. They would have been killed, or tortured by the NKVD, or exiled to Siberia. My Dad would likely never have been born, and I of course would never have come into existence.

The story of Ukrainian refugees in WWII parallels that of the Syrian refugees today in so many ways. Like the Syrian refugees, my grandparents were destitute, and they would never have been attractive to a country like Canada on a purely economic metric. Like the Syrian refugees, they practiced a different religion (Eastern Orthodox) and came from a country with no history of liberal democracy and civil liberties, which in the opinion of the nativists and xenophobes, would have made them impossible to integrate into the fabric of Canadian society. Of course, they are now among the over 3 million Ukrainians and their descendants in Canada, who have been integral to the building of the affluent, peaceful country we now live in. In retrospect it seems beyond absurd to have thought they couldn’t integrate. It is equally absurd to think that Muslim immigrants from the Middle East would be any less likely to do so today.

The most remarkable thing about my family’s story is, in fact, how it is the eminently ordinary Canadian story. Unless you are First Nations, many of you could trace a similar story. Most recently Croats and Bosnians and Somalis and Tamils, and before that Ukrainians, Poles, Jews, Mennonites, Hungarians, Germans. Baltic peoples, Italians, Greeks, Koreans, Vietnamese, Chinese, Cambodians, Laotians, Africans, South Americans, Mexicans, Afro-Caribbean. Even before them, it was starving Irish and persecuted Scots, runaway slaves escaping the South to freedom via the underground railway, and British loyalists fleeing retribution at the hands of revolutionary Americans—so many different peoples fleeing from war, persecution, famine or at the very least material circumstances so dire they propelled them to uproot their families and their entire lives and risk an often hazardous journey to the frozen, sparsely populated and totally alien country of Canada. In every one of these refugee waves, the xenophobes and nativists said Canada should shut the door, that we could not afford to take them in, that these culturally dissimilar people would not integrate, etc. In every single case, the xenophobes and nativists were completely wrong.

This is why I find the immigration and refugee policies of our current government so unfathomable. As you may have seen, Canada has refused to accept more than a token number of Syrian refugees. In the 4 years since the Syrian civil war broke out, Canada has taken in 2,400 Syrian refugees—2,400 out of more than 4 million. On top of this, our government has dramatically reoriented our immigration and refugee policies, jettisoning that humanitarian ethos that had formerly played such a large part in how we designed such policies. Our current government has dramatically reduced the number of successful refugee applicants. The only recourse for unsuccessful applicants is an appeal, a legal right the Conservatives attempted to strip away before the Canadian courts intervened, declaring such a policy patently unconstitutional. In order to save an utterly insignificant couple of million dollars, they stripped health coverage from refugee claimants, before the courts again intervened, declaring such policies “cruel and unusual”. This government apparently even contemplated dramatically reducing the number of eligible refugees that would be accepted with health problems, including most disturbingly, refugees who had been tortured. As the Canadian Immigration and Refugee Bar has noted, never before have Canadian policies on refugees been so mean and so incompetent.

In defence of these policies, I’ve heard a lot of dubious arguments trotted out. First, I’ve heard how economically unfeasible it is to accept more than a token few refugees. This line of argument fundamentally misunderstands how an immigrant society like Canada became prosperous in the first place. Going forward, this country’s greatest economic challenge is demographic—we have an aging population, with fewer and fewer working-age adults capable of supporting the pensions and universal health care of retirees. And of course, the argument that accepting refugees would bankrupt our country is utterly belied by the successive waves of immigration responsible for erecting the Canadian welfare state. The arguments in defence of our miserly treatment of refugees are economically misguided, morally indefensible and certainly unsupported by any empirical assessment of the history of migration to Canada.

I’ve also heard that it is essentially pointless to take in refugees without addressing the source of the problem, which in this simplistic rendering of the immensely complicated Syrian civil war, boils down entirely to ISIS. Whatever your position on the military coalition against ISIS, it is incredibly naive to suggest that somehow Canada is going to alter the refugee dynamic in the Middle East by dropping a few bombs in Syria. Canada could play an immeasurably larger humanitarian role by opening our doors, like Germany and Sweden and others have done.

Finally, I’ve also heard a great deal about why this shouldn’t be a partisan issue. I agree. In fact, until this present government, it historically never was a partisan issue. The short lived conservative government of Joe Clark accepted 70,000 Southeast Asian ‘boat people’ in 79-80. There was a bipartisan consensus that extended from every Canadian government from Diefenbaker’s conservatives, to the Pearsonian-Trudeauvian brand of internationalist social liberalism, to the neoliberal governments of Brian Mulroney and Jean Chretien. It is only Stephen Harper that decided to build a political brand on a mean-spirited lack of compassion to refugees.

The plight of the Syrian refugees, their hunger, their desperation, their unimaginable suffering, was not that long ago our hunger, our desperation, our suffering. So many of us Canadians were once refugees, or economic migrants. Slamming the door on them now is to, in a very literal sense, forget who we are.