Painting a snapshot of 1L and the narratives that are excluded from the realm of law using literary prose

The OFC’s recent excavation of the history of the Women’s Caucus has prompted the Feminisms of Osgoode Past to revisit their relatives at the law school today. The body of documents, zines, and ephemera we have unearthed are sometimes uplifting and even enlightening, and sometimes offensive or laughable to our all-knowing 2015/2016 sensibilities. No matter their substance, Osgoode’s history reminds us that this school is a reflection of the things we bring into it, feminism among them, and that to honour ourselves is to acknowledge every aspect of ourselves—warts and all.

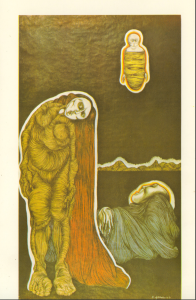

In the second edition of the OFC’s ongoing series inspired by the Women’s Caucus/OFC archives, I invite the cross-examiner from Judy Grahn’s poem “A Woman is Talking to Death” (artwork pictured) to coerce a series of confessions for your reading pleasure. These are no typical confessions. They illustrate the narratives that are excluded from testimony on the witness stand, from the scrutiny of our learned future colleagues, and from the personae we construct for ourselves over small talk here in our very own Gowlings Hall. As the titular allusion to Monet’s seminal artwork might suggest, this unconventional cross-examination paints several personal impressions of Osgoode at the beginning of my own career as a law student.

***

[Testimony in trials that never got heard]

[Have you ever committed any indecent acts with women?]

This school is one long hallway, illuminated by slanting rectangles of yellow when the sun is right, and I wonder if students’ eyes are forever in shadows. Many people are wound tight, anxious, and I feel dread when they talk at me, trying to tell me about the spiny-legged fears that are running around in their nervous bodies. When I say goodbye, I am worried that they will thread their arms through mine in an inescapable embrace. People here don’t look like me—our respective baggage disfigures us into singular, unrecognizable things—and I wonder if I look heavy to them when I speak.

I think that if I say I’m very adept at carrying things—that I won’t weigh them down, that they will be even less convinced. I keep the conversation light, like yellow rectangles that don’t quite reach their eyes, and I pray they don’t dig into the fat of me. Too sharp law students, razor blade gazes always ready to gouge.

[Have you ever committed any indecent acts with women?]

The thought of the Library makes me sweat.

Early on, I decide to save a little money for gas and borrow my books. But as I walk through Gowlings, I find myself hesitating before those great glass doors.

When I was a girl, I saw lobsters in the windows of Chinese storefronts in Kensington. I saw smiling faces in smutty aprons throw squirming lobsters in big, silver pots with a little splosh. Until recently, scores of hungry happy people were content believing that crustaceans lacked the robust central nervous system and receptors to feel pain.

Imagine the collective gag reflex as science revealed the mortifying opposite to be true.

Nodding, smiling chefs grinning back at little girls to the soundtrack of a dozen shrill, bug-eye bursting shrieks at a frequency inaudible to the laughing, happy agents of death.

A dozen expressionless faces, none of them betraying the torture and terror cooking their insides.

I breathe deep and buy the damn books instead.

[Have you ever committed any indecent acts with women?]

In October, I volunteer to act as a client in a mock session for a second year family law class. In this story, I am a determined but hurting woman who cannot reveal to my potential counsel all of my truths. I come to them, sitting at a table too big for the narrow classroom it is in. As I walk its length towards these two men, every step feels heavier, burdened down by things that don’t get mentioned in light conversation. I come to them seeking a divorce from my husband, but these students who interview me have to earn the story, so I am told I must withhold. I read the case the night before and, as I sit there at that table, the script starts churning viscous like cement inside of me and I think I have swallowed the real woman whose life informed this make-believe. At the end of our hour, the men applaud me for my delivery, and I wish I never see them again. I laugh with them, so loud and forceful; I laugh so hard my eyes smart. I’m gasping. From that point on, the shorter of the two, who sounded so compassionate before the timer buzzed, calls me Superstar when he passes me in the halls, and the little woman in me feels used.

Q: Miss Grahn, have you ever committed any indecent acts with women?

A: Yes, many. I am guilty of allowing suicidal women to die before my eyes or in my ears orunder my hands because I thought I could do nothing, I am guilty of leaving a prostitute who held a knife to my friend’s throat to keep us from leaving, because we would not sleep with her, we thought she was old and fat and ugly; I am guilty of not loving her who needed me; I regret all the women I have not slept with or comforted, who pulled themselves away from me for lack of something I had not the courage to fight for, for us, our life, our planet, our city, our meat, our potatoes, our love. These are indecent acts, lacking courage, lacking a certain fire behind the eyes, which is the symbol, the raised fist, the sharing of resources, the resistance that tells death he will starve for the lack of the fat of us, our extra. Yes I have committed acts of indecency with women and most of them were acts of omission. I regret them bitterly.